‘We’re Using the Future for a Fiscal Dumping Ground.’ Beware Trillion-Dollar Deficits

By Jack Hough

Photo: New Studio

There’s no snooze button on the national debt clock, though you wouldn’t know it by the way public alarm has quieted as the situation grows worse.

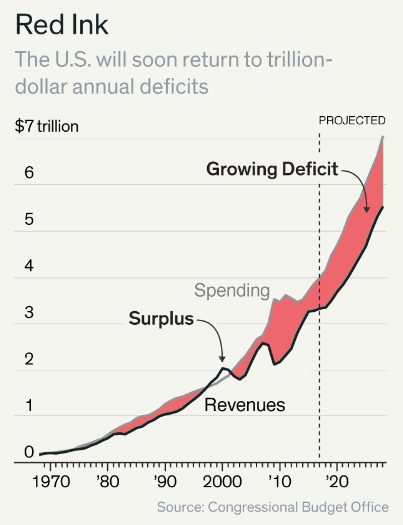

October begins a new fiscal year for the U.S. government—and a faster ballooning of how much it owes. Barring a behavioral miracle in Congress, trillion dollar yearly budget shortfalls will return, perhaps as soon as the coming year. And unlike the ones brought by the financial crisis and Great Recession of 2007-09, these will start during a period of relative plenty, and won’t end.

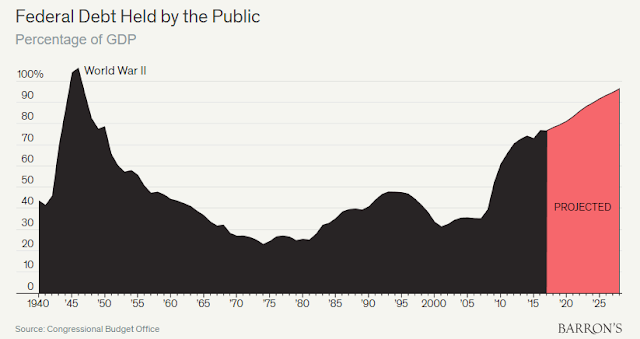

Debt held by the public, a conservative tally of what America owes, will swell from $15.7 trillion at the end of September, or 78% of gross domestic product, to $28.7 trillion in a decade, or 96% of GDP.

Those estimates, provided by the Congressional Budget Office, are based on reasonable assumptions about economic growth, inflation, employment, and interest rates, but they leave out some important things. They assume that the nation’s need for increased infrastructure investment, estimated by the American Society of Civil Engineers at $1.4 trillion through 2025, goes unmet. They don’t account for the possibility of another financial crisis, or war, or a rise in the frequency or severity of natural disasters, and they assume that some Trump tax cuts will expire in 2025.

.

There is no clear milestone that marks the moment a country loses control of its finances, but consider how the bar has already been lowered for what seems possible in Congress. Even debt scolds no longer talk seriously about America paying down what it owes, or holding the dollar amount steady. The new path of fiscal prudence involves containing debt at some manageable percentage of GDP, and the opportunity for that is slipping.

“It’s a generational issue,” says Robert Bixby, executive director of the Concord Coalition, a nonpartisan group focused on the debt. “We’re using the future for a fiscal dumping ground.”

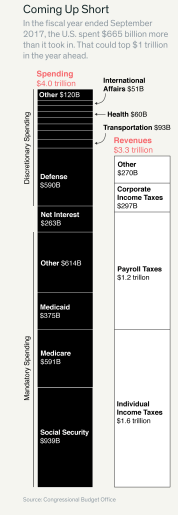

Just holding the line at 78% of GDP over the next three decades would require finding massive, immediate savings in the budget—$400 billion over the coming year, rising gradually to $690 billion by 2048, using 2019 dollars. In comparison, America spent $590 billion in fiscal 2017 on defense, and $610 billion on all other discretionary items. (The rest of the $4 trillion in spending went for mandatory programs, such as Social Security and Medicare, and for interest on the debt.)

This past week didn’t inspire confidence. House Republicans introduced Tax Cuts 2.0—bills touted as “permanent tax relief for families and small businesses.” But a fresh decline in federal revenue and the resulting increase in the deficit will hardly come as relief to the taxpayer whose share of the national debt, now $164,000 on average, is already set to top $250,000 in a decade. The 2.0 round has little chance in the Senate, and appears mostly designed to force Democrats into voting against “relief” ahead of midterm elections. Investment bank UBS forecasts a 60% likelihood that Democrats will take the House in November, with Republicans keeping the Senate, the most likely result of which will be gridlock. Here’s hoping a mixed Congress can get something done, because even now, there remain plausible paths to fiscal reform.

Both Sen. Mike Enzi (R., Wyo.), chairman of the Senate Committee on the Budget, and Rep. Steve Womack (R., Ark.), chairman of the House Budget Committee, declined to talk with Barron’s about the debt.

This is no panicked warning for stock and bond investors, because the chances of a debt-driven blowup appear low in the near term. In fact, the biggest risk related to markets is that placid conditions will add to complacency. With the 10-year Treasury yield near 3%—around half its average of the past half-century—it’s clear that there remain eager buyers for America’s debt.

The problem is that we could be wrong about the limited investment risk. “I don’t think bonds adequately reflect what at some point in the future, with high probability, will be trouble in bond markets and with interest rates, due to our fiscal situation,” says Robert Rubin. Treasury Secretary from 1995 until mid-1999 in the Clinton administration, he was one of the last in that position to oversee budget surpluses. Rubin points out that Greek government bond yields were modest for years before spiking past 25% in 2012, during a debt crisis.

If the party that has long branded itself as fiscally conservative—and showed off a debt clock during the 2012 Republican National Convention, in a call to action—now has little interest in containing deficits during good times, the result could be a costly backlash during the next bust. Bond guru Jeffrey Gundlach oversees more than $120 billion in investor assets as chief investment officer at DoubleLine Capital, and was early to predict Donald Trump’s election win and the shift to faster debt growth. He has called the act of expanding deficits while the Federal Reserve is raising interest rates a “suicide mission.”

Gundlach expects investors to buy Treasuries if the threat of deflation returns “as a Pavlovian reaction” and notes that a high short position in them could even set up a short squeeze. “After that, you might find yourself with a more radical reaction,” he says. “There could be elevated acceptance of a universal basic income—just send everyone money.” Already, there is a movement afoot among a some economists on the left who point out that governments that borrow in money they print can’t technically go bankrupt, and say that budget deficits are, if anything, too small.

When deficits are large, money tends to be spent on “stupid things,” says Maya MacGuineas, president of the nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. “If you don’t have constraints, you don’t think about how to spend wisely.” MacGuineas calls the debt “the most predictable crisis we’ve ever faced,” but says spotting the tipping point will be difficult, because much depends on other countries, and their appetite for our debt. “We can borrow a lot more if we’re still the best-looking horse in the glue factory,” she says.

The gross national debt, a figure commonly used for debt clocks, topped $21 trillion in March. We focus here on debt held by the public, which subtracts amounts owed by one part of the government to another, such as Treasuries held in the Social Security trust fund. The debt is what we owe. The deficit is the amount by which we go further into the hole each year.

Not all deficits are bad. The $1 trillion-plus deficits America ran for four years ending in 2012 helped shore up its financial system and prevent a deep recession from turning into a prolonged depression. Keynesian economics calls for deficit spending and lower taxes during economic slumps to stimulate demand, with the money recouped through surpluses during good years. That last part isn’t happening, however. “Now Keynesian seems to mean you stimulate all the time,” says Gundlach.

If the debt were growing more slowly than the economy—or put differently, with the deficit projected to total 4.6% of gross domestic product over the next year, if GDP were climbing faster than 4.6% in nominal terms—the burden could be said to be slowly diminishing. As it turns out, the economy is estimated to have risen faster than that on an annualized basis last quarter, but it got a boost from temporary factors, including a rush by America’s trading partners to stock up on goods ahead of new tariffs.

Over the coming 10 fiscal years, the CBO estimates real annual GDP growth averaging about 1.7%, and nominal growth of 4.0%. Deficits, meanwhile, are expected to rise from here, averaging 4.9% of gross domestic product annually over the coming decade. The projected downshift in economic expansion owes in part to a widely accepted demographic challenge: the ongoing retirement of the baby boomers, which will hold back expansion of the labor force, a key determinant of GDP gains.

A few commonly prescribed fiscal remedies won’t, on their own, do the job: cutting foreign aid; cracking down on waste, fraud and abuse; and reining in welfare. Foreign aid, using a broad definition that includes things like military assistance to fight terrorism, is around $50 billion a year—a sliver of needed savings. Waste, fraud and abuse are surely all lurking in the budget, but the Government Accountability Office puts improper payments for all federal entities at $141 billion in fiscal 2017, and the challenge is driving that figure lower without spending mightily on new compliance efforts. Consider welfare a catchall term for means-tested programs that are part of mandatory spending, like Medicaid; the earned-income tax credit; and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, sometimes still referred to as food stamps. Then the combined dollar amount is significant—an estimated $742 billion this fiscal year. But it is dwarfed by the $2.1 trillion that will be spent on mandatory programs that aren’t means-tested, like Social Security, military retirement programs, and most of Medicare.

“There’s no low-hanging fruit, politically,” says Concord Coalition’s Bixby. “It’s the entitlement programs, and the baby boomers have already begun to collect.” The boomers are sometimes described as a metaphorical pig in a python, but Bixby points out that while Social Security’s deteriorating fiscal condition could stabilize after the boomers retire, it will not reverse, and that Medicare’s challenges will keep growing. “It’s more like a telephone pole in a python,” he says.

Like Bixby, former Treasury Secretary Rubin points to cutting Medicare cost growth and raising federal revenue as jobs 1 and 2 in fixing the deficit. “You need comprehensive health-care reform that is focused on costs,” says Rubin. “If you can reduce cost growth in Medicare and Medicaid, even without cutting entitlements, you’re halfway there,” he says. The other half is revenue. During the last, brief flirtation with budget surpluses, from 1998 through 2001, yearly federal receipts were 19% to 20% of GDP. Over the next several years, that figure is expected to bottom at 16.4% before beginning to rebound—if certain tax cuts expire.

There is little consensus around the theory that deficit-fueled tax cuts goose growth enough to pay for themselves over time. But there is every reason to believe that fiscal reform will be good for growth, as interest costs are contained and private investment takes the place of government borrowing. Even under the scenario of merely holding the debt to 78% of GDP for the next 30 years, the CBO estimates that gross national product per person would end up 4.5%—or about $4,100—higher, compared with baseline assumptions.

The last bold effort to deal with the debt was the Simpson-Bowles plan drafted by a bipartisan commission appointed by President Obama in 2010, when debt was 61% of GDP. It called for nearly $4 trillion in deficit reductions through 2020, with big cuts to discretionary spending, changes for Social Security and Medicare, and a lowering of personal and corporate tax rates, combined with purging the tax code of breaks. That would have put debt on a course toward an estimated 40% of gross domestic product by 2035. The final draft, titled “The Moment of Truth,” didn’t win enough support to come to a vote in Congress.

.

The last big fiscal success, the “Clinton surpluses” of 1998-2001, can be traced in part to the efforts of President George H.W. Bush. He was faced with a dangerous combination of a weakening economy and high interest rates. To convince the Federal Reserve to lower rates, he needed smaller budget deficits. A Democratic Congress wouldn’t agree to spending cuts without higher tax revenue. But Bush had famously promised, “Read my lips, no new taxes” during the 1988 Republican Convention. In the end, he reached a bipartisan deal that included about $2 in spending cuts for each $1 in added revenues, including from a tax hike on high earners. That deal helped cost Bush re-election in 1992. President Clinton followed up with a deficit-cutting budget in 1993.

The deficit fell from 4.5% of gross domestic product in 1992 to near-breakeven five years later, before swinging to surpluses. The lesson of what might rightly be called the Bush-Clinton surpluses is that budget reform isn’t a job for narcissists or glory seekers, because the public outrage forms immediately, and the benefits don’t become clear until much later, by which time others will have arrived to help collect the high-fives.

The good news is that, if the courage to tackle the deficit somehow visits Capitol Hill, financial markets appear likely to cooperate, at least for a while.

In a recent analysis, economists at J.P. Morgan studied historical debt defaults, bailouts and inflation spikes since World War II in countries that resemble the U.S. economically. They found that the probability of these things occurring within any five-year period was less than 6%. Statistically, the link between debt levels and crises is surprisingly weak. That is, crises have occurred in countries with lower debt/GDP than the U.S. has now, and some countries with higher debt/GDP have avoided crises. Many crises corresponded with specific currency problems that, for the U.S., seem less relevant.

The economists’ takeaway is that it’s “too early to worry about a U.S. sovereign debt crisis,” but also that “we should not ignore lessons from history on the fragility created by debt.”

Andy McCormick, head of the U.S. taxable bond team at T. Rowe Price, is similarly confident about the near term. “The next six months to two years—no problem,” he says. “When debt hits 100% of GDP, it could shake people up, but it’s a little too long-term for me to put into portfolios.

If he’s right, there’s an opportunity, while bond yields and interest costs remain low, to put aside partisan antics and take bold action to restore fiscal order. It won’t be easy, but it will never be this easy again.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario