The Scan That Saved My Life

After decades of exercise and healthy eating, a reporter’s blocked artery came as a shock; the debate over testing to prevent debilitating strokes

Reporter Thomas M. Burton, right, spoke this month with Bruce Perler, a professor of vascular surgery at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. On June 27, Dr. Perler performed an operation to unblock one of Mr. Burton’s carotid arteries. Stephen Voss for The Wall Street Journal

“Let’s talk about your test results,” my neurologist said.

She looked as if she had good news. Instead, it was shocking.

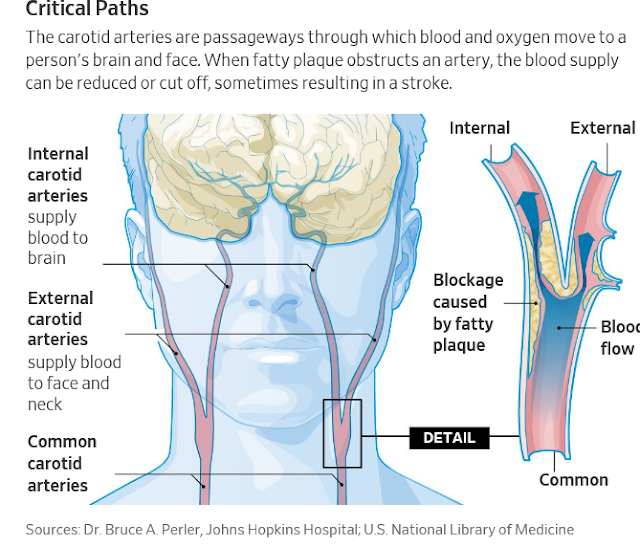

The carotid artery on the left side of my neck, one of the brain’s two main sources of blood and oxygen, was clogged with fatty plaque, the doctor said. The artery was almost completely blocked.

There must be a mistake, I thought frantically. I exercise and am healthy and young. Actually, I’m 68, but, you know, a young 68. You are in danger of a major stroke, she said, and need an operation. Immediately.

The irony wasn’t lost on me. As a journalist covering the medical field, I have spent years writing about strokes, most of which are caused by clots blocking blood flow to the brain. Now I faced the unnerving question: Am I going to become a weird punch line? As in: Did you see that the guy who writes all those stories about strokes just had a big one?

A blocked carotid artery didn’t seem possible for an active person like me. I’ve never smoked. I’ve run, lifted weights or done something aerobic like playing tennis pretty much every day of my life. I watch what I eat. I even wrote an article about how I kept my bad cholesterol in check with diet and exercise, not medication.

While I’m addicted to cheese, and my weight has climbed some, I’ve eaten foods like salmon and oatmeal with fervor for more than 20 years. So I figured I was exempt from medical crises.

The diagnosis made me reconsider dilemmas that had once seemed academic. For example, should older Americans be screened for blocked carotid arteries?

Sources: Dr. Bruce A. Perler, Johns Hopkins Hospital; U.S. National Library of Medicine

Clots cause about 700,000 strokes that lead to 130,000 deaths annually in the U.S. and are the primary preventable cause of disability, according to the American Stroke Association. Carotid disease is a main cause of those strokes—nearly 200,000 strokes a year, vascular specialists say. Yet 80% of those patients have no symptoms before the strokes.

In 2014, a U.S. task force concluded that people with no symptoms don’t have to be screened for carotid disease, saying that the risks, such as poor surgery, “outweigh the benefits.” But the task force—a panel of private doctors assigned by law to help set U.S. medical policy—focused on screening in the general population, not older patients.

The task force said there aren’t enough carotid-caused strokes to warrant screening everyone. Of course, not everyone with carotid blockage will get surgery; thousands of people with the condition can benefit from drug therapy.

My experience, along with some evidence from screening of thousands of individuals, raises questions about the task force’s conclusions. The Society for Vascular Surgery recommends screening people over 65 with coronary disease, high blood pressure or a history of smoking.

The task force generally supports screening Americans for breast cancer, with 253,000 new cases in women and 41,000 estimated deaths annually, as well as colorectal cancer, with 135,000 new cases and 50,000 deaths a year. Government and private insurance pay to screen for these illnesses, but not for carotid screening of non-symptomatic people, which can cost about $70 a person.

After hearing the jarring news about my dangerously blocked carotid, I faced a big decision. My wife Christa and I live near Washington, D.C. Our daughter, Maddie, was supposed to be married in San Francisco in June, a week after the neurologist told me I needed surgery right away. Suddenly the prospect of being at the wedding seemed iffy.

Conventional wisdom says that among the 65-and-older set, only those with symptoms should be tested. That often means individuals who have had mini-strokes, which tend to be brief periods in which the patient has something wrong on one side of the body, usually for a few minutes. Symptoms often include slurred speech, temporary vision loss, a one-sided facial droop and arm or leg weakness or numbness.

Vascular surgeon George Lavenson Jr. wrote in 2012 in the Journal for Vascular Ultrasound that among 22,146 people screened for carotid disease during four public screening campaigns between 2001 and 2006, about 7.5% were found to have blockage of 60% or more—enough to warrant treatment with medication.

“It is hard to understand how many leaders in the medical profession can object to a one- to two-minute accurate screen of seniors that can find the 7.5% with silent carotid artery disease,” Dr. Lavenson said. Those patients can be “evaluated and managed to prevent them from being one of the 700,000 clot-caused strokes we continue to have annually.”

Most doctors would have put me in the asymptomatic, or less-risky, category. But five years ago, I went out for a run of about 7 miles along the Potomac River. At the end of the run, my right leg started shaking. That seldom happened again until the past few months, when it started recurring more often, along with shaking in the right arm.

My physician, Joel Taubin, recommended a neurologist, Rhanni Herzfeld, of the Neurology Center in Washington. She prescribed tests to discern the cause of the shaking, perhaps a pinched nerve, incipient epilepsy, a neurological disorder or a tumor. The results ruled them all out.

Then an MRI of my head showed a few white spots on the left side. Dr. Herzfeld wondered if I might have had some “silent strokes,” sending tiny bits of artery plaque floating to my brain—and now appearing as white spots on the scan. Fatty plaque accumulates in most people’s arteries, and can form clots that break off and can cause strokes.

Dr. Herzfeld ordered a carotid ultrasound of the arteries on both sides of my neck. It’s a quick, painless and very accurate scan. Moments later, we were talking in her office. My right carotid artery was perfectly clear, she said. The left was almost completely blocked and I needed immediate surgery to clear it.

I asked if we could treat the obstruction with anti-platelet medication, such as Plavix.

“No, your blockage is just too extensive,” Dr. Herzfeld said. She recommended that Bruce A. Perler, a professor of vascular surgery at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, do the procedure.

The effectiveness of carotid-artery surgery in people without symptoms—but major blockage—was established two decades ago by the Asymptomatic Carotid Artery Stenosis trial, funded by the National Institutes of Health. It showed, in hospitals in the U.S. and Canada, that the risk of stroke or death in surgery patients after a median 2.7 years was 5.1%, less than half that of people treated only with drugs. An international study published in 2010 in the Lancet showed similar benefits from surgery.

I consulted with other doctors, including one who said, “This isn’t quite an emergency, but it’s urgent.”

The operation is serious, with the rates of stroke and death within 30 days after surgery totaling about 2.4% in major studies examined by the task force. The task force noted that this typical measure can be as high as 5% at some low-volume hospitals.

People considering this operation should ask their hospital, surgeon or academic medical center about their rates of stroke and death after surgery. Few hospitals and surgeons in the U.S. publish their individual results. Dr. Perler’s rate was well under 1%. He said my risk of stroke was 10% to 15% over five years, probably in the first year.

A week before Maddie’s wedding, my wife and I met with Dr. Perler at Johns Hopkins. On the drive to Baltimore, we called Maddie. She sounded frightened and I told her maybe I wouldn’t need surgery—or could put it off. We also told her brothers, Jamie and Will, and her sister, Samantha, what was going on.

Dr. Perler’s test confirmed Dr. Herzfeld’s findings: I definitely needed surgery. My artery was almost completely obstructed by “echolucent” plaque—a type that can easily form clots, break off and cause strokes.

We discussed timing. Dr. Perler’s next surgery day was June 18. That would leave me four days to recover before the wedding. He warned that I would be “miserable” doing that. But his next surgery day after that wasn’t until June 27.

“You can safely wait until next week,” he said, “but I wouldn’t wait two months.” Then he added the words I remember most: “We’ll take good care of you.”

My wife and I decided on June 27—and headed to San Francisco for the wedding. It was an untraditional ceremony with no white veil or a parade of bridesmaids. Maddie wore a champagne-colored, beaded dress. I have never seen her so happy—except maybe when she was playing My Little Pony as a 6-year-old. I was simply happy to be there.

Tom Burton and his daughter, Maddie, at her wedding to Dan Powers at San Francisco City Hall in June, less than a week before Mr. Burton’s surgery to unblock a carotid artery. Photo: Christina Richards Photography

On the morning of June 27, Dr. Perler started operating at 7:30. Within two hours, he had cleared the plaque from my carotid artery. Later, he told me it was so clogged—about 99%—he couldn’t even detect a pulse in it.

When I woke up, I was relieved to see that my eyes and fingers all worked. I could think and speak clearly. I was even able to complain to the nurses about how lousy I felt.

I spent two days in intensive care, with my blood pressure surging at times. About two weeks after the operation, I felt pretty normal. I’ve resumed running and weight-lifting. I recently played golf for the first time since the surgery and feel great.

But mostly I feel lucky to have gotten a test that may have saved my life.

Getting Screened

A national company, Life Line Screening, will do a carotid screen for $70, or with other tests such as for aortic aneurysms, for $149.

Hospitals’ accredited labs will do carotid ultrasound tests typically for $200 to $300, but usually only on a doctor’s order.

Insurers, private and government, generally will pay only if the patient has symptoms, including a mini-stroke.

The Society for Vascular Surgery’s site, vascular.org, can direct people to specialists who can do testing.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario