The Bolivarian wave

A rude reception awaits many Venezuelans fleeing their country

Turmoil in Latin America is causing mass migration

PACARAIMA is a speck of a town in the Brazilian Amazon on the border with Venezuela. Recently, it has been the entry point for tens of thousands of Venezuelans fleeing hunger, violence and hyperinflation at home. Most continue by foot 220km (135 miles) on the motorway to Boa Vista, the capital of the state of Roraima, where they struggle to survive by unloading lorries, hawking crafts and selling sex. About 2,000 of the poorest have stayed in Pacaraima, pitching tents in the streets. That has strained the town’s resources and the tolerance of its 12,000 inhabitants.

On August 17th several men, apparently Venezuelans, robbed and beat a shop-owner. At an anti-immigration march the next day, hundreds of locals threw stones at migrants’ tents and set fire to their belongings. More than a thousand Venezuelans fled into the jungle or back over the border. Their makeshift homes burned to the ground. Brazil’s president, Michel Temer, sent 60 troops to restore order.

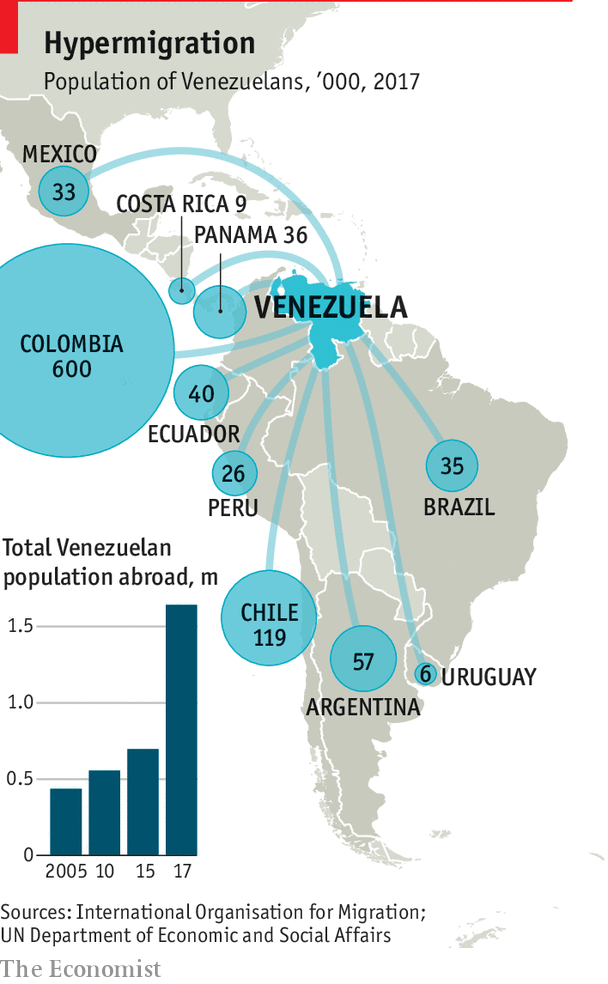

Though the Venezuelan exodus sometimes seems as invisible as tiny Pacaraima, it is the biggest movement of people in Latin America’s recent history. Since Venezuela’s economy began to slump in 2014 under Nicolás Maduro, a socialist strongman, perhaps 2.3m Venezuelans have sought refuge in neighbouring countries. The size of the exodus rivals those of war-ravaged Afghanistan and South Sudan.

Unlike many rich countries, which have been closing their doors to migrants from northern Africa and the Middle East, Latin American governments have mostly let people in. Left-wing governments in the early 2000s relaxed immigration laws, says Luisa Feline Freier of the Universidad del Pacífico in Lima, Peru. The right-of-centre governments that succeeded them in several countries maintained these policies as a rebuke to Mr Maduro’s regime.

As Venezuela’s crisis has worsened, the number of people fleeing has surged. Unlike those in earlier waves, the newer migrants tend to be poor rather than middle class. The exodus has prompted some countries to impose restrictions on their borders. Ms Freier fears that Latin American countries will soon become as wary of immigrants as many European ones.

On August 16th the government of Ecuador announced that it would turn away from its border Venezuelans not carrying passports, saying they posed a security risk. Most of these were heading towards Peru, which is receiving a record 5,000 Venezuelans a day. It imposed its own passport requirement with effect from August 25th and said it would not issue work permits to Venezuelans who arrive after October. Many do not carry passports. Because of a paper shortage and software problems, getting one can take two years. A bribe to jump the queue can cost up to $1,000.

Venezuelans are not the only migrants provoking unease. In Costa Rica, the backlash is directed at Nicaraguans, who are escaping the repression by Daniel Ortega, Nicaragua’s president, of opposition protests. From April to July 23,000 migrants sought asylum in Costa Rica, which has a tradition of generosity to refugees. On August 18th hundreds of protesters in San José, the capital, chased Nicaraguans in a park and set fire to their flag. The United Nations reprimanded the instigators.

Chile’s strong economy makes it a magnet for migrants. The number of foreigners registered there has risen almost five-fold in a decade, to 750,000 last year (about 4.5% of the population). Perhaps 300,000 more were living in Chile illegally. Last year the number of Venezuelans in Chile grew by about 100,000. Many had sold all their belongings to pay for the 12-day bus trip. More than 100,000 also came from Haiti, the Americas’ poorest country. A poll last year found that two-thirds of Chileans wanted to restrict immigration.

Sebastián Piñera, who became Chile’s president in March this year, responded by tightening its relaxed immigration policies. He abolished a visa that immigrants could apply for after entering as tourists and placed restrictions on tourist visas for Haitians. Venezuelans are being treated more generously; they can get a “democratic responsibility” visa allowing them to work.

The main holdout against the trend towards harsher treatment of migrants is Colombia, by far the largest destination for Venezuelans. Around 900,000 have moved there, a third of those this year alone. Juan Manuel Santos signed a decree that “regularised” 442,000 undocumented Venezuelans before he left office as president on August 7th. For the next two years they will be able to work, get health insurance and study—benefits that 1.5m other Venezuelans living illegally in Colombia and elsewhere have a hard time claiming. The new conservative president, Iván Duque, has not changed Mr Santos’s policy. Colombia’s “migration director” criticised the restrictions in Peru and Ecuador, and restated Colombia’s commitment to helping Venezuelans.

In part, Colombia’s generosity is a form of gratitude to Venezuela, which took in more than 700,000 Colombians during the country’s half-century war with the FARC guerrilla group. The war ended in 2016. Some 250,000 Colombians have now come back from Venezuela, adding to the strain of coping with migrants.

Activists and some politicians are trying to keep doors ajar. After Ecuador’s ombudswoman called its passport requirement “cruel” and filed a complaint with the supreme court, the government said it would not apply to children accompanied by parents who have passports. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) said in March that many Venezuelans qualify as refugees under international law. It is urging governments to issue humanitarian visas and work permits. Aid from richer countries like the United States “could make the difference between Venezuelans being supported and Venezuelans being blocked at borders”, says Chiara Cardoletti-Carroll of the UNHCR. Ecuador has called a meeting of leaders from the region in September to discuss a co-ordinated response to the crisis.

But diplomacy may not ease tensions in the host countries. In Roraima, the army has taken over responsibility for providing shelter, food and health care to the Venezuelans. So far, though, the government’s policy of “interiorisation”—sending them to richer states with more jobs—has failed. Just 800 migrants have been moved.

One reason is “institutionalised xenophobia”, says a Roraima official. This is sharpened by a general election due to take place on October 7th. On August 19th Roraima’s governor renewed a plea to Brazil’s supreme court to shut the border. That did not stop hundreds of Venezuelans from coming on August 20th. They had little choice, says Jesús López Fernández de Bobadilla, a Spanish priest who serves breakfast to 1,600 migrants. “Over here it’s purgatory, but over there it’s hell.”

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario