The Hidden Risks of China’s Private Sector Debt Crisis

Better health for China’s state-owned titans has come at a steep cost

By Nathaniel Taplin

China has only stemmed the bleeding at its debt-laden, inefficient state sector with large-scale transfusions from private enterprise. The result will eventually be a less efficient economy.

Chinese firms are punting on their debt again: There were 20 bond defaults in the first seven months of 2018, according to Wind Info, nearly as many as in the whole of 2017. Deteriorating finances come at a bad time, with trade tensions rising and the yuan sharply down.

When defaults jumped in 2016, the companies were mainly state-owned enterprises, or SOEs.

Now they are nearly all private. On the face of it, this is less worrying: The overleveraged property sector aside, private-sector woes in China are less systemically dangerous because SOEs still dominate the bond market.

But, in the long run, the situation could prove worse for the Chinese economy. SOEs have improved their health partly at the expense of more efficient private companies. If this persists, it will mean structurally lower income growth—and precipitate a financial crisis anyway if private firms and households can’t get rich quickly enough to keep subsidizing their state cousins.

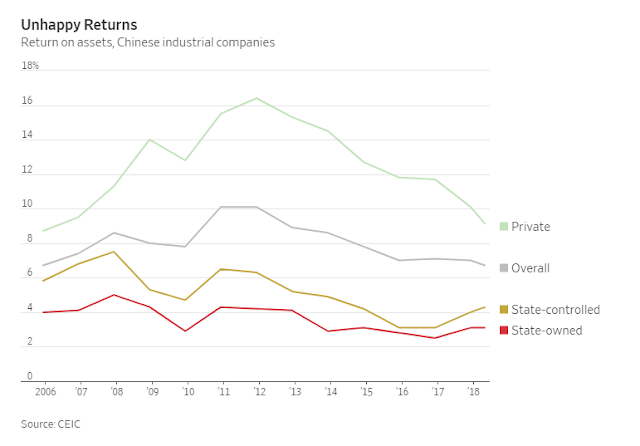

Private industry has been taking it from all sides recently. It bore the brunt of forced factory closures last year: Iron and steel investment as a whole fell 7% in 2017, but private investment in the industry was down 10%. With less competition, the quasi-public players are doing better: Return on assets in the state-controlled industrial sector hit 4% in late 2017, the highest since 2014.

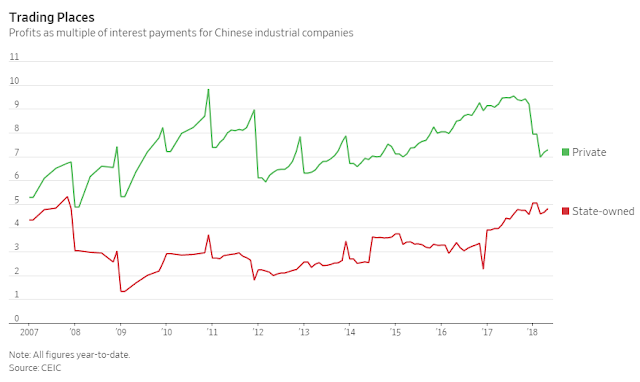

Moreover, shutting down private factories—and simultaneously curbing shadow banking, which the private sector relies on—has done nothing to brighten banks’ view of private sector credit. The result has been a fall in SOEs’ interest burden and a rise in private firms’ borrowing costs. In late 2016, industrial SOEs’ profits amounted to barely three times their interest payments, while private industrial firms made nine times what they paid in interest.

Now industrial sector SOEs make five times interest payments due, while private firms make seven.

Private industry as a whole is still well able to finance itself. Although return on assets has fallen 2 percentage points since 2016, mirroring the rise in SOE returns, it remains at 9%—well above the weighted average bank lending rate of 6%. As long as property prices don’t plunge, it’s unlikely that a private sector debt crisis will trip up China’s financial system.

The closed iron and steel plant of Shougang Capital in Beijing. Shutting down private factories has done nothing to brighten banks’ view of private sector credit. Photo: greg baker/Agence

Still, the defaults highlight how a steadier state sector has come at a cost to private enterprise.

There’s little sign that China’s regulatory blitz of the past two years has done anything to improve the efficiency of credit allocation.

China’s July manufacturing purchasing managers’ index was, excluding the Lunar New Year period in January and February, the weakest in over a year. The next credit stimulus is now on its way.

Beijing needs to ensure that this time the medication reaches the right patients.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario