Dear Reader,

My biologist son recently brought a cold virus back from Tokyo. Therefore, it was probably inevitable that I’m now recovering from a minor respiratory tract infection (RTI). On the upside, it gave me time to think about what virus-borne diseases are teaching us about curing aging.

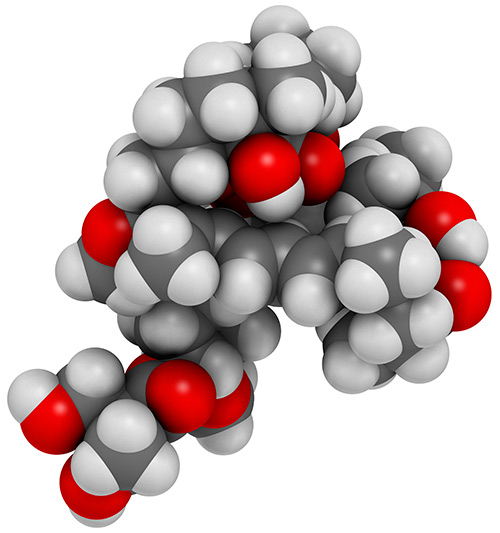

I’ve written a lot about rapamycin and will again in the future. The accidental discovery of this molecule, produced by bacteria in the soil of Easter Island to combat fungi, is one of the most important milestones in scientific history. Someday, monuments will be built celebrating the enormous impact of the rapamycin molecule on humanity’s health and longevity.

Source: Getty Images

Rapamycin’s anti-fungal properties were largely forgotten when it was discovered that the drug suppressed immune system function in organ transplant recipients better than existing treatments. The drug was first approved under the name Rapamune for that purpose.

While transplant recipients have obviously benefited from rapamycin, the molecule has had a far greater impact on the science of aging.

Initially, researchers were concerned that organ transplant patients taking rapamycin might be susceptible to otherwise minor wounds and infections. The term “immune suppression” always made me think of the movie Bubble Boy, based on the true story of David Vetter. Born without an immune system, he lived his short life in a sterile environment because any pathogen could have killed him.

However, rapamycin didn’t turn off people’s immune systems. Instead, doctors wary of infection observed unexpected and positive effects in older patients. My cousin-in-law, for example, was prescribed a Japanese version of rapamycin following a kidney transplant, and his graying hair began to regrow in its original color.

During this period, scientists began to view the immune system as a two-edged sword. Inflammation, the mechanism used by the immune system to fight pathogens, could also cause harm, especially in older people. Gerontologist Claudio Franceschi coined the term “inflammaging” to describe chronic, low-level overactivation of the immune system.

This was a new way of looking at immunosenescence, the recognized decline of the immune system’s function in the aged. One example of immunosenescence is that older people often fail to develop immunity when given vaccines.

Many scientists assumed older people’s immune systems were failing because they were “weak,” but that term is misleading.

A better way to think of immunosenescence is that older immune systems have hair triggers and are constantly responding to minor threats and false alarms.

Overextended and exhausted by constant activation, they’re less able to deal with real problems such as infections or cancers.

Overextended and exhausted by constant activation, they’re less able to deal with real problems such as infections or cancers.

Dr. Joan Mannick—who now works as chief medical officer for resTORbio, but back then worked for pharma giant Novartis—suggested that turning down the dial on the immune system via a version of rapamycin (RAD001) might be the answer.

In a 2014 paper in Science Translational Medicine, she showed that “RAD001 enhanced the response to the influenza vaccine by about 20% at doses that were relatively well tolerated.” Additionally, she and her collaborators found improvements in T cell function.

Even the Elderly Can Benefit from Rapamycin

The benefits from calming overactive immune systems are easily observable in animal trials. Mice given low doses of rapamycin experience health and lifespan increases of about 20%. The most exciting aspect of this discovery is that older animals given rapamycin get almost the same effects.

It appears that rapamycin provides two benefits, even in elderly people. First, it reduces inflammation, which is a source of constant cellular damage. Second, it allows the immune system to repair real problems. That’s why we see gray hair restored to its original color and wrinkles fade.

By the way, I heard that the rapamycin experiment on older mice was accidental—like so many other aspects of this story. Researchers had intended to dose their lab subjects at middle age but encountered some sort of bureaucratic delay. Because mice only live a few years, the animals were already old in human terms when the experiment was able to proceed. The researchers expected little but were amazed to see the mice visibly rejuvenate.

The theory that overactive immune systems contribute to inflammaging was further confirmed by resTORbio, which licensed the Novartis rapamycin IP. The company recently released phase 2b trial data on its rapalogs, which showed reduced incidence and severity of respiratory tract infections in high-risk elderly patients.

This is encouraging because the World Health Organization has downgraded Tamiflu (oseltamivir) as a treatment for influenza, removing it from its essential-medicines list.

The reason: there is little to no evidence that Tamiflu is effective in treating the flu, despite $18 billion in annual sales. The resTORbio data, on the other hand, indicates that rapamycin and the rapalogs—if dosed correctly—are a much better solution to RTIs, including influenzas.

However, the bigger picture is that the knowledge gained from rapamycin and the rapalogs has already led to new discoveries. Behind the scenes, other scientists are focused on strategies that will make the 20% increases in healthspan delivered by rapamycin trivial.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario