The Curse of the Great Recession, the Train Crash, and the Singularity

A recent Wall Street Journal article points out that “Americans entering retirement are in worse financial shape than the prior generation, for the first time since Harry Truman was president.”

For some context, Truman took office in the last few months of World War II, the deadliest and most expensive conflict in history.

During that war, about 75% of America’s total economic output and expenditures were spent on the conflict, leaving only a quarter of the country’s GDP for all other activities. Investments in anything other than war bonds plummeted, and normal goods—from food and clothing to gasoline—were strictly rationed. Any extra rubber, paper, and metals acquired before the war were collected and given to the military.

It’s no mystery why Americans retiring in the wake of “the war to end all wars” were less prepared than the previous generation. That’s not the case with the current generation of retirees whose savings rate has fallen over the last decades.

Social Security and Medicare Can’t Save You

Social Security and Medicare Can’t Save You

The sad part is that while people’s hopes are increasingly pinned on Medicare and Social Security to help them stay afloat financially, just a few weeks ago, we saw official government warnings that those programs will be forced to reduce benefits by 2026 and 2034, respectively. Underfunded public- and private-sector pension funds add another level of pain.

In short, we aren’t saving enough for our individual and collective retirements. This is borne out by the numbers, presented below in a graph by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

As an economist, I’m fascinated by any long-term change in human behavior. So what might be the reason for those individual and societal retirement deficits?

Some analysts attribute the reduction in people’s savings to interest rates, which have dropped since the 1980s, but I don’t think that alone explains why people are failing to provide for their old age. Nominal interest rates don’t actually measure return on investment because they reflect and correct for inflation.

The answer, I believe, is hinted at in the WSJ article I mentioned before. Referring to current retirees, the writer observes, “They have high average debt, are often paying off children’s educations, and are dipping into savings to care for aging parents.”

Greater Life Expectancy Creates Huge Financial Burdens

Unlike previous generations, many people today are forced to support their parents much longer—often while helping their children too.

Among financial planners, there is a saying, “Pay yourself first.” That means you should put money into your own savings before you spend on anything else.

This is a great idea, but it may not be practical for most people. Longer lifespans, unique to our times, have made it more likely that working families will face pressures to help both parents and children.

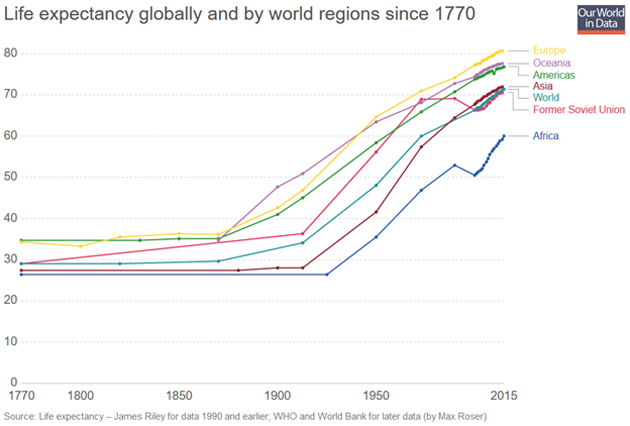

I’ll include only one chart, from Our World in Data, to illustrate the increases in life expectancy caused by the Industrial Revolution, which was promptly followed by a scientific one.

Source: Our World in Data

Another reason why the financial and emotional burden of supporting older people has increased is that birthrates have fallen so precipitously in recent generations.

When families consisted of four, five, or more children, the responsibility for helping the aged and ailing parents was divided among siblings. Today, according to the same WSJ article, “More than 40% of households headed by people aged 55 through 70 lack sufficient resources to maintain their living standard in retirement, a Wall Street Journal analysis concluded. That is around 15 million American households.”

And this is just one aspect of the retirement house of cards, a fragile debt structure maintained only by the assumption that something will happen down the road that makes everything better. Even if your own retirement is fully funded, you are not immune to the disruptions that will hit the entire economy when that house of cards collapses.

I know a lot of people don’t believe it’s going to happen, but I’ve been here before.

No One Wants to Listen—Just Like in the Runup to 2008

In the early 2000s, I was among the few contrarian economists cautioning that federal monetary policies were creating unsustainable mortgage and real estate bubbles.

It wasn’t pleasant standing in opposition to the financial industry’s consensus that everything would be cool. Most journalists, politicians, and other financial analysts interpreted the warnings as political attacks. Some who predicted that things would end badly were accused of creating economic instability by undermining consumer confidence.

Another difficult aspect for those predicting a downturn was that the bubble persisted longer than most people expected. Many people who heeded the warnings stayed on the sidelines while others profited from the ever-inflating bubbles. As a result, many of the “Cassandra” economists lost friends and clients.

That changed, of course, when the bubble popped and economic growth went negative in 2007. When the dust had cleared, America’s household net worth crashed from over $65 trillion to less than $50 trillion, and the ranks of the jobless grew by 8 million. The S&P 500 lost more than half its value, ravaging the life savings of tens of millions of people who trusted the highly paid analysts of the mainstream financial industry. Too many investors who had been rich on paper found themselves in default or worse.

El Jefe John Mauldin was one of the few prominent economists in the financial world who warned about the bubble. To this day, I meet people who tell me his advice saved them fortunes.

Unfortunately, the mountain of Social Security and Medicare debt is much bigger than the mortgage and housing bubbles. When it collapses, and it will, the consequences will be much worse.

Societal aging and the unwillingness to address it have been the biggest drivers behind deficit spending and debt in the developed world. Putting aside all ethical and legal issues, one fact remains: we’ve made promises that can’t be kept... and therefore won’t.

The Poison Is Also the Antidote

Ironically, the only solution to the problems created by longer lifespans is even longer and healthier lifespans. If we can stay healthy and productive for most of our lives, individual wealth will increase significantly because we’ll have longer to earn and save.

And because the most expensive diseases are age-related, healthcare costs will go down. By delaying or reversing old age, the old-age dependency ratio is repaired, budgets will be balanced and the debt paid off.

This isn’t science fiction or wishful thinking. The biggest obstacle to a revolution in healthcare isn’t scientific—it’s political and psychological. Though more scientific breakthroughs are coming, they aren’t needed to fix the demographic problem.

I’ve personally talked to scientists who calculate that if older people used optimal doses of vitamin D3, rapamycin, and a good multivitamin, it would increase healthspans enough to balance the federal budget within a few years. The next generation of anti-aging therapeutics will be even more effective.

I’m sure of this, but I’m not sure when it will happen. Unfortunately, it seems to me that our institutions are once again in denial, as they were prior to the Great Recession.

If this cloud has a silver lining, it is that many of us will live long enough to see the recovery when longer lives and other innovations create a new era of health and affluence.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario