Bello

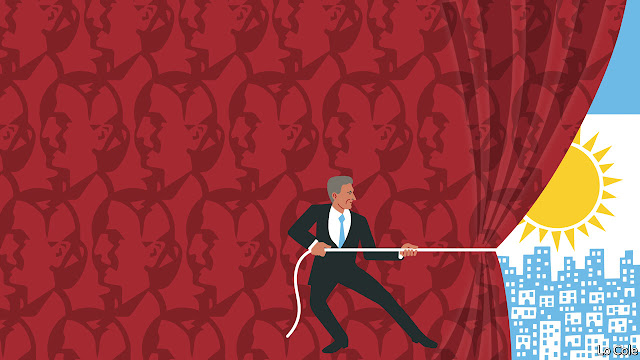

Mauricio Macri fights Argentina’s tradition of handouts for votes

The president is changing the country’s political culture

JUST off Leonardo da Vinci Avenue, a long street of modest shops and foul-smelling gutters in the district of La Matanza outside Buenos Aires, stands La Juanita, a co-operative. Founded by unemployed workers in 2001, it occupies a former school. It runs a free kindergarten, a microcredit programme, a call centre and, nearby, a large community bakery, all with the aim of helping the unemployed get work. Since Mauricio Macri, a former businessman of the centre-right, was elected as Argentina’s president in 2015 La Juanita has become part of a political experiment.

La Matanza is in the heart of the conurbano, a sprawl of poor and crime-ridden suburbs around Argentina’s capital which contains some 10m people. It was a bastion of support for Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, the populist Peronist president from 2007 to 2015. Peronism long controlled the conurbano through clientelism, providing handouts in return for political loyalty. This system stopped offering social mobility, argues Héctor “Toty” Flores, a founder of La Juanita. The conurbano has become home to an underclass preyed on by drug gangs and dirty cops.

Mr Macri has attracted attention for his effort to stabilise and open Argentina’s economy while avoiding shock therapy. Yet in the medium term his impact on his country’s politics may be even bigger. The victory of Mr Macri’s Cambiemos (“Let’s Change”) coalition in a legislative election last October means that everybody except diehard kirchneristas now thinks he will become the first elected president who is not a Peronist to finish his term since the movement was founded by Juan and Eva Perón in the 1940s. Barring accidents, he has a good chance of winning a second term in 2019. “He has created a new equilibrium in the party system,” says Juan Cruz Díaz, a political consultant.

It helps Mr Macri that an ally, María Eugenia Vidal, unexpectedly won election as governor of Buenos Aires province (which includes the conurbano) in 2015 against a weak kirchnerista candidate. Mr Macri and Ms Vidal promise a new kind of politics, with two pillars.

The first is more efficient delivery of public services to places that lack them. Mr Macri has built a rapid-transit bus line in La Matanza. “People didn’t even demand sewerage here because they couldn’t get it,” says Mr Flores. “In a year they will have it.” Officials say that they are able to spend more on public works, even while reducing the fiscal deficit and taxes, because they are cutting out waste and corruption. Marcos Peña, Mr Macri’s chief of staff, cites a big tender for medicines this month, which he says came in 80% below the previous cost.

La Juanita now gets official support. A dozen of its members draw government salaries. The labour ministry has set up a small office there to help the unemployed draw up CVs. An IT training school will open next month. Ms Vidal’s people see La Juanita as a model. “If they can do it here, we can do it in other places,” said Gabriela Besana, a visiting provincial legislator.

The second change is philosophical. The state will do different things. Mr Macri’s people stress pre-school education and changing the physical and social environment in poor areas. The government will soon require jobless welfare recipients to attend school or training programmes. “We don’t ask anything [else] in return,” says Mr Peña. “Clientelism demands the subjection of the poor, rather than lifting them out of poverty,” he adds. “Our main aim is to offer these people the dignity of the middle class.”

Plenty could go wrong. Cambiemos has won over former Peronist political operators and risks lapsing into the same methods. La Juanita could itself become a vehicle for clientelism. Mr Flores is a congressman for Cambiemos. Then there is corruption. “Off the record, this is a very honest government,” says a political scientist, who fears any such statement in Argentina is a hostage to fortune.

Mr Macri’s bet on economic gradualism could also be derailed. The middle class—Mr Macri’s own political base—has felt the squeeze of higher utility bills as subsidies are withdrawn, but not yet many benefits from an economy that is growing at a rate of less than 3% per year. On the streets of La Matanza scepticism still outweighs hope. The divided Peronists may unite around more moderate policies. Perhaps the biggest risk is that success goes to the heads of Mr Macri’s team of bright young technocrats.

Yet the potential prize for Cambiemos—and for Argentina—is great. Mr Macri is building a movement founded on the values of opportunity and aspiration, not dependence. If he succeeds, his example will echo around Latin America.

Home

»

Argentina

»

Politics

» MAURICIO MACRI FIGHTS ARGENTINA´S TRADITION OF HANDOUTS FOR VOTES / THE ECONOMIST

viernes, 6 de abril de 2018

Suscribirse a:

Enviar comentarios (Atom)

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario