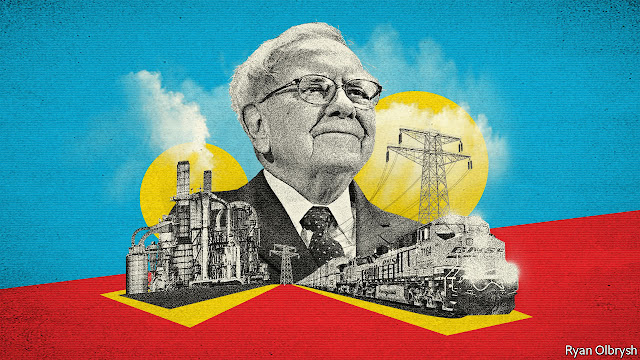

INSIDE WARREN BUFFETT´S DEAL MACHINE / THE ECONOMIST

Schumpeter

Inside Warren Buffett’s deal machine

Berkshire Hathaway has evolved into an acquisition engine. The returns look pedestrian

SOME things about Warren Buffett never change, including his non-stop jokes, famous annual letter and his reputation as the world’s best investor. What is less understood is that over the past decade Mr Buffett’s company, Berkshire Hathaway, has sharply altered its strategy. For its first 40 years Berkshire mainly invested in shares and ran insurance businesses, but since 2007 it has shifted to acquiring a succession of large industrial companies.

In some ways it is hard to criticise Berkshire. Its shares have kept up with the stockmarket and its standing is exalted. It is the world’s seventh-most-valuable publicly traded firm (the other six are tech concerns). But Mr Buffett’s behemoth is a puzzle. Its recent deals have had drab results, suggesting a pivot to mediocrity.

It has been quite a spree. Since 2007 Berkshire has spent $106bn on 158 firms. The share of its capital sunk into industry has risen from a third to over half. The largest deals include BNSF, a North American railway, Precision Castparts (PC), a manufacturer, various utilities, and Lubrizol, a chemicals business. Further transactions are likely. Berkshire has roughly $100bn of spare cash. In his latest letter, published on February 24th, Mr Buffett complains about high valuations but says there is a possibility of “very large purchases”. Berkshire thinks of itself as a friendly buyer to which families and entrepreneurs are happy to pass on their crown jewels. There is something comforting about its mission to be a home for old-school businesses run by all-American heroes.

Yet it is not an obvious formula for superior performance. Berkshire must pay takeover premiums and has $64bn of goodwill. It enjoys no synergies of the sort corporate buyers claim and unlike private-equity firms does not overhaul management at its targets. There is no clear reason why being owned by Berkshire improves performance. Mr Buffett has largely missed the past decade’s tech boom, the big force behind the stockmarket.

Can Berkshire turn water into wine? Schumpeter has attempted to answer this by crunching the numbers, using a certain amount of guesswork. There are two ways to capture how Berkshire creates value, both of which Mr Buffett has in the past endorsed. One is measuring Berkshire’s own book value and how this increases. The other is to examine its “look through” profits, which are made up of the earnings of its wholly-owned businesses as well as its share of the earnings from the firms in which it owns small stakes. Over the past five years its book value has grown by a compound annual rate of 11%. Berkshire’s look through return on equity (ROE) has usually been 8-9% (all further figures exclude the impact of a $29bn one-off gain booked in 2017 relating to America’s law slashing corporate tax).

Those results are worthy of Mr Buffett, but the next step is to split Berkshire into two areas and examine the larger part—its acquired industrial businesses, spanning its railway, energy, utility, manufacturing, services and retail units. These have a total book equity of $191bn, most of which was built up in the past decade. By this measure Berkshire is the second-largest industrial concern in America. The industrial arm’s operating performance is bog standard and, once you include the goodwill, its ROE is a weak 6%, down from 9% in 2007 before Berkshire shifted course (these sums exclude the amortisation of intangible assets, which is in accordance with how Mr Buffett assesses profits).

The industrial businesses’ lacklustre record mean they account for about 60% of Berkshire’s sunk capital but have generated only about half of its look through profits, and 40% of its growth in book value over the past five years. For the five big industrial companies where figures are consistently available, total profits have risen by 4% a year since 2012, which is no better than a basket of similar peers. Profits at BNSF, for example, have risen only just above inflation and in line with other railways. Speaking to CNBC on February 26th, Mr Buffett suggested that a sixth business, PC, had not met its own internal targets.

Since Berkshire cranks out an annual return of about 8-11% a year overall, the other area of its business, its financial operations, must have done much better. These include insurance underwriting, leasing, stock-picking, gains on derivatives and lucrative one-off transactions struck by Mr Buffett, for example when he bought bonds issued by Goldman Sachs and General Electric during the financial crisis. Overall, Berkshire’s financial arm has a solid average ROE of 11%, achieved with low leverage.

Why, then, is Berkshire making large industrial acquisitions? There is a chance that profits will grow faster in future, pushing up the low ROE of the acquired businesses, yet most of them are mature. Or Berkshire may hope that selected acquisitions, when valued in line with their listed peers, will show a big rise in their value since being bought, which accounting profits do not capture. BNSF, which Berkshire bought in the depths of the crisis in 2009, has yielded an annual return of about 15% if measured in this way. However the other deals are unlikely to look nearly as good: two thirds of them (by value) took place after the end of 2011, once markets had bounced back from the crash.

Crossroads in Omaha

Berkshire has three possible paths forward. One is that Mr Buffett and his partner, Charles Munger, return cash to shareholders and accept that Berkshire must be less ambitious. The two men do not seem ready for this. A second is that they do more big takeovers now, with stockmarkets high. That would likely depress Berkshire’s returns for years and make it more reliant on fireworks from its financial arm. The third path is that Mr Buffett and Mr Munger sit and wait, hoping for a stockmarket crash, when Berkshire’s war chest will let it pick up bargains that make better returns than its recent acquisitions have done. Twenty years ago this strategy would have been uncontroversial, but the two men are aged, respectively, 87 and 94.

Berkshire is enough of a conundrum to perplex even the world’s greatest value investor.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario