Donald Trump has been lucky with the US economy

He is taking credit for the continuation of a post-crisis recovery begun under Obama

Martin Wolf

So I think you have a brand new United States.” That was Donald Trump’s boast in his speech to the business elite gathered at the World Economic Forum in Davos. So how, if at all, is America “new”?

How might this belief of Mr Trump’s affect his global economic agenda? Why did Mr Trump, who shocked Davos, by stating at his inaugural that “Protection will lead to great prosperity and strength”, become only the second US president to visit the annual meeting in Switzerland, after Bill Clinton, in 2000?

Mr Trump’s main aim, it was clear, was to assert that “after years of stagnation, the United States is once again experiencing strong economic growth”. Moreover, it is “open for business”. These and similar claims on employment and consumer and business confidence ran through his speech. It is true that the US economy is strong; it is not true that this follows years of stagnation.

Between the second quarter of 2009 and the end of 2016, the US economy grew at a compound annual rate of 2.2 per cent. Over the past four quarters, it grew by 2.5 per cent. That is not a significant change. The big shift in growth — downwards, unfortunately — was after the financial crisis of 2008. The economy is 17 per cent smaller than it would have been if the 1968-2007 trend had continued. Since its recovery, in 2009, it has been on a far slower trend. This may change, but has not yet done so. The same is true for labour productivity, whose growth remains low. (See charts.)

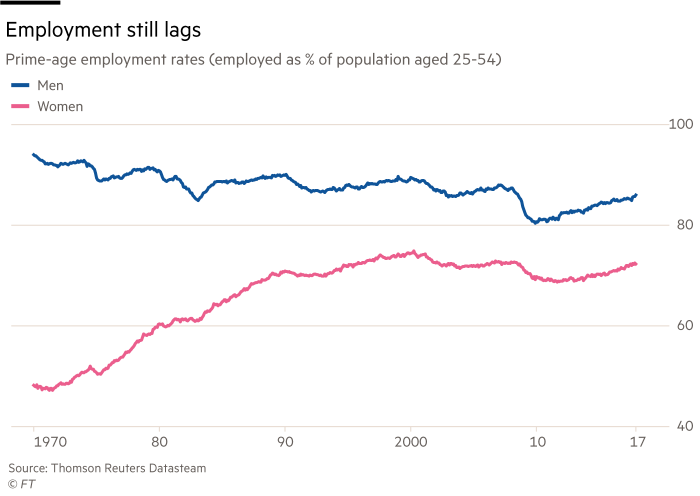

The unemployment rate has indeed fallen under Mr Trump, from 4.7 per cent in December 2016 to 4.1 per cent in December 2017, a very low rate by historical standards. But this is a continuation of the downward trend since 2010. If anybody deserves the credit, it is the Federal Reserve, for policies too often condemned by the Republicans. Eighty-six per cent of men aged 25-54 had jobs in December 2017. This is a percentage point higher than a year earlier, but 5.6 percentage points higher than in January 2010. Unfortunately, it is still below the previous cyclical peaks of nearly 90 per cent in 1999 and 88 per cent in 2007. The proportion of prime-aged women with jobs is also below levels in 2000.

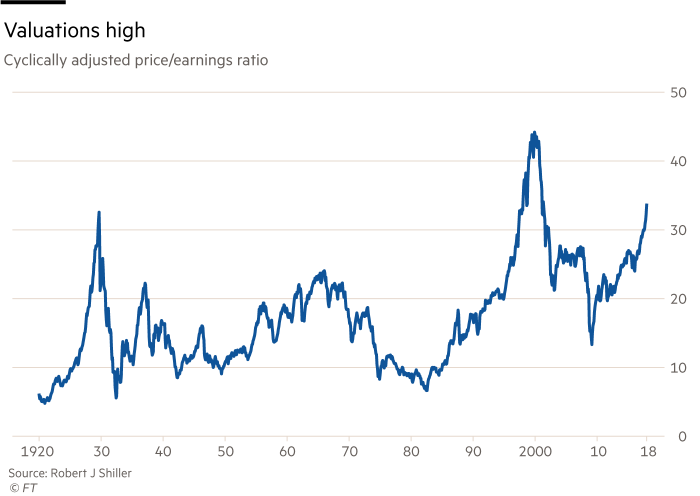

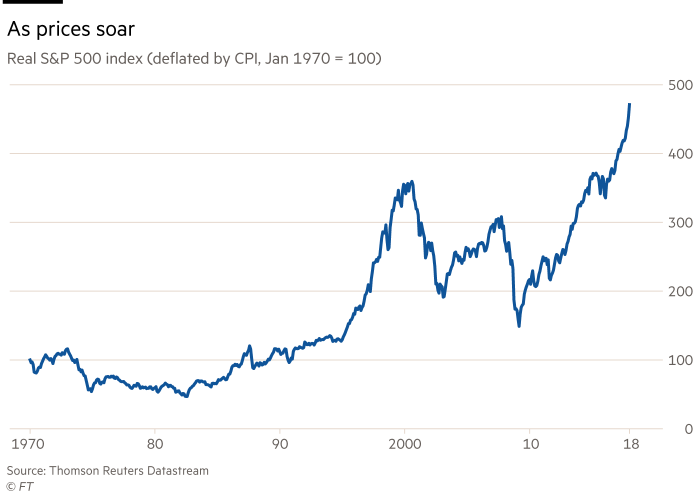

Mr Trump is particularly enthusiastic about stocks, claiming that the market is “smashing one record after another”. This is not wrong. In terms of Robert Shiller’s cyclically adjusted price/earnings ratio, valuations of the US market are as high as in 1929 and have been exceeded since then only by the exalted valuations of 1998, 1999 and 2000. The rise of the market in the last year is quite remarkable, given how high it already was. But this should be a worry, not a boast. Mr Trump may soon come to regret lauding a high stock market. It is at no president’s beck and call.

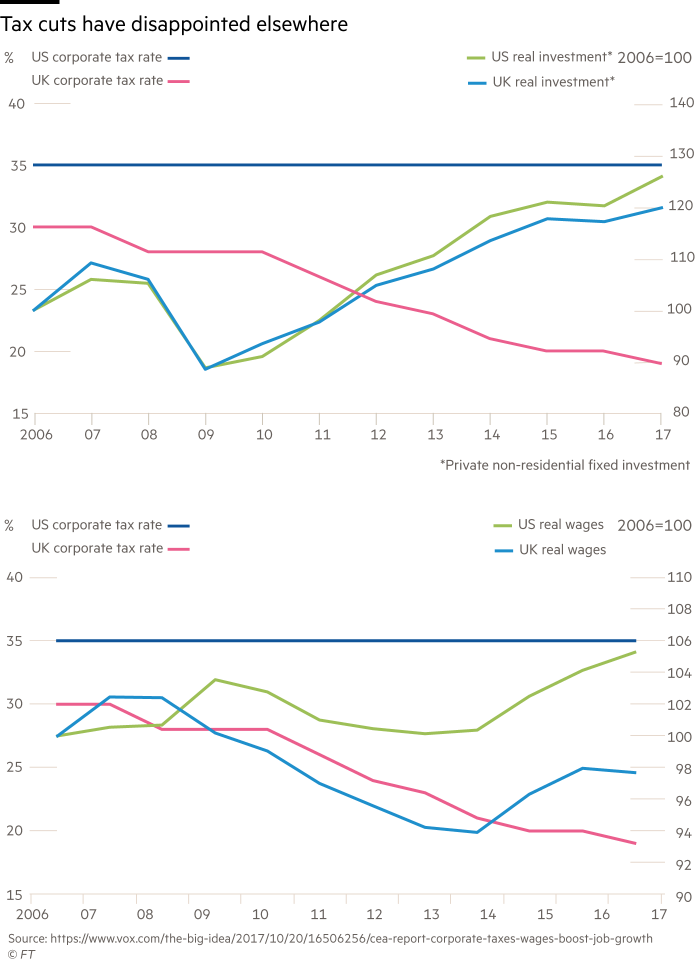

An argument for hoping that better times will soon be here is the huge tax cut for business. It is quite unlikely, however, that this will unleash a flood of investment and higher underlying economic growth. A more plausible view is that it will mainly increase stock prices, wealth inequality and the speed of the competitive race to the bottom on taxation of capital. British experience on this is sobering. The slashing of UK corporate tax rates to 19 per cent has done little for investment or median real wages. The hope that it proves any different in the US is likely to be disappointed.

Briefly, Mr Trump is taking credit for the continuation of a post-crisis recovery begun under his predecessor. This is no “brand new” economy. He has been lucky. Provided the stock market does not blow up, he may stay lucky. Yet the question is how a lucky Mr Trump will behave. Will a man who feels he is on a winning streak be more demanding or more accommodating?

A particular concern is trade policy. On this, Mr Trump has stated: “We support free trade, but it needs to be fair and it needs to be reciprocal. Because, in the end, unfair trade undermines us all.” This is not new rhetoric.

The optimistic view is that we are going to see more of the sort of measures announced last week on solar panels and washing machines. These are foolish, but standard. Even the renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement might be a damp squib. Now that the other 11 participants in the Trans-Pacific Partnership have, to their credit, agreed to go ahead, Mr Trump even says that: “We would consider negotiating with the rest, either individually, or perhaps as a group.”

The pessimistic view is that the administration is hooked on fundamentally crazy doctrines: the US trade deficit is the result not of macroeconomic imbalances, but of cheating on trade policy; in addition, the way to eliminate this deficit is via new bilateral deals with all important trade partners. This approach would blow up the multilateral trading system. It is also incompatible with market economics. Only planned economies could attempt the bilateral balancing in which Robert Lighthizer, the US trade representative, and his master apparently believe. An aggrieved superpower armed with such a benighted doctrine could do immense damage to the global economy and international relations.

How then should we evaluate the confident and emollient Mr Trump we saw in Davos? His boasts may be empty, but he has indeed been lucky in inheriting an economy enjoying a strong post-crisis recovery. The economy should remain his friend, so long as he does not trust too much in the stock market.

That is good news for him. A strong US economy is good news for the world, too. A confident Mr Trump might not be. The question is how he reacts. Will he be more reasonable or more intransigent? His speech did not provide all the answers. Uncertainty still reigns.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario