Dancing with danger

Europe’s populists are waltzing into the mainstream

They and their ideas are both being picked up by established parties

ON AN icy January morning, twinkly lights and the glow from chic cafés illuminate Hässleholm’s tidy streets. The employment office opens its doors to a queue of one. Posters in shop windows invite locals to coffee mornings with immigrants asking: “What will you do to make Sweden more open?” At first glance, this small town fulfils every stereotype about the country: prosperous, comfortable, liberal. But last year it became the centre of a political storm.

Mainstream Swedish politicians have refused to co-operate in any way with the Sweden Democrats (SD), a right-wing populist party with extremist roots, since it was formed in 1988. In 2015 Fredrik Reinfeldt, a former prime minister and then still leader of the centre-right Moderates, described the SD’s leadership as “racists and the stiffly xenophobic”. But a year ago the Moderates used SD support to oust Hässleholm’s centre-left local government and elect Patrik Jönsson, the SD’s regional leader, vice-chair of the new council. In November the council adopted an SD budget that would cut spending on education and social care for immigrants and build a new swimming pool for locals instead. “We just want to shut Hässleholm’s doors,” announced Mr Jönsson. Per Ohlsson, a columnist on Sydsvenskan, the local newspaper, is alarmed: “I get a growing feeling that liberal democracy is something we have taken for granted for too long.”

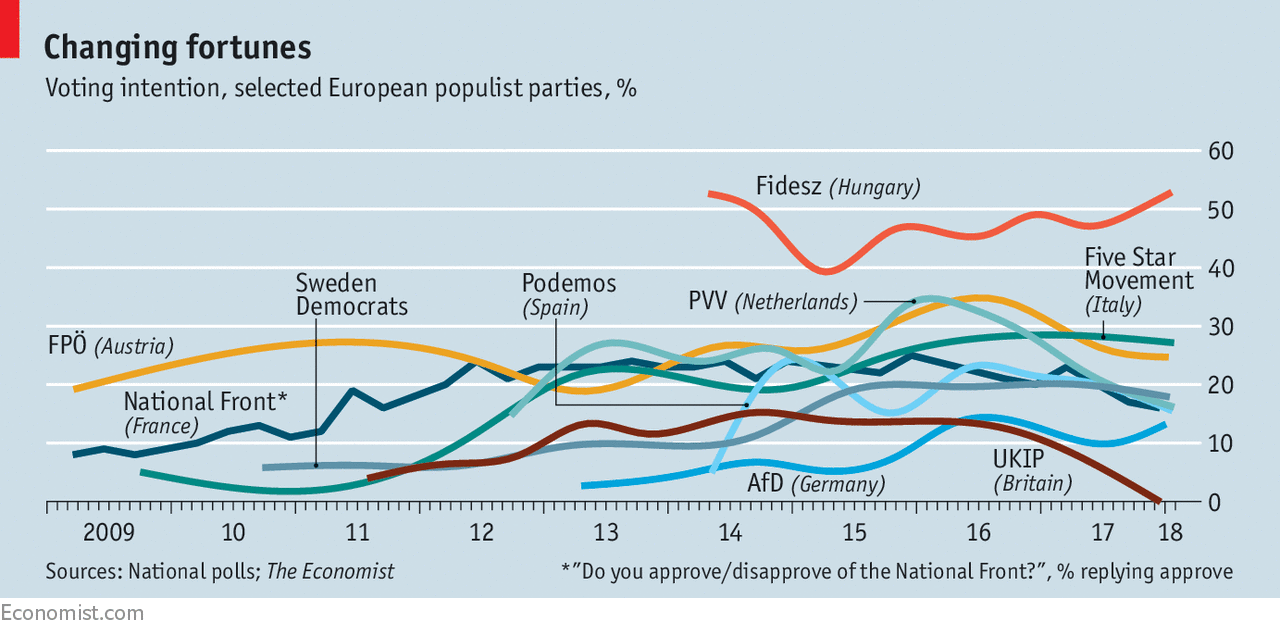

Some European politicians saw 2017 as a welcome setback to the rise of populism across the continent. After a 2016 in which support for parties like the SD hit record highs, and England and Wales voted for Brexit, polls showed the populists’ popularity falling (see chart). Marine Le Pen of the Front National (FN) lost the French presidential election to Emmanuel Macron; her party fared poorly in the subsequent elections for the National Assembly. The Alternative for Germany (AfD) made it into the Bundestag for the first time, but not to a degree that truly threatened moderate politics. Two far-right “Freedom” parties, the PVV in the Netherlands and the FPÖ in Austria, did worse than expected in their national elections.

The continuing rise of populism, though, is something to measure decade by decade, not year by year. The financial crisis and the large influx of refugees contributed to a spike, but Euro-populism has been growing quite steadily since the 1980s. According to a new study by Yascha Mounk of Harvard University and others for the Tony Blair Institute, the populist vote in an EU state was, on average, 8.5% in 2000. In 2017 it was 24.1%. This quantitative increase is producing qualitative shifts in the continent’s politics. As Hässleholm shows, populists are no longer shunned by the democratic mainstream as a matter of course; they are increasingly called into coalitions, co-opted and copied.

Defining populism is notoriously subjective, but political science provides some guidelines. Jan-Werner Müller of Princeton University singles out its exclusive claim to represent a “morally pure and fully unified people” betrayed by “elites who are deemed corrupt or in some other way morally inferior”. Populism attacks judges, journalists and bureaucrats it deems not on the side of the people. It speaks the language of silent majorities, national humiliations, rigged systems; of “We are the people” (Germany’s anti-Islam PEGIDA movement), “Take back control” (Brexiteers), “This is our country” (the FN)—and, elsewhere, “Make America great again”.

Cas Mudde of the University of Georgia notes that populism is a “thin” ideology. It can have hosts on the left as well as the right and even create hybrids of its own, such as the Five Star Movement (M5S) which is topping Italian opinion polls in the run-up to the general election in March. It can also be practised by politicians whose parties are not avowedly populist. Such politicians can subscribe to a more or less monolithic and exclusive vision of “the people”; they can defend minority groups, the judiciary and the free press to a greater or lesser extent; they can choose honesty about policy trade-offs over convenient scapegoats more or less frequently. Their parties can inch along the spectrum over time. So can whole societies.

Take Hungary. The Fidesz party led by Viktor Orbán, the country’s authoritarian prime minister, grew out of the anti-communist movement and governed the country as a fairly conventional conservative party around the turn of the century. But partly under pressure from Jobbik, an extreme right-wing party founded in 2003, and increasingly citing “the will of the people”, Mr Orban has taken to demonising immigrants and minorities (particularly Muslims), attacking the judiciary and disenfranchising sources of dissent. He is demanding that, at the parliamentary election to be held in April, the voters give him a mandate to take on George Soros, the Hungarian-born, America-based billionaire who founded the Central European University in Budapest and who, Mr Orbán claims, has a secret plan to flood the country with Muslims.

Most political scientists now consider Fidesz a full-blown populist outfit. Elsewhere the entangling of mainstream parties with populist policies and the populist style takes place in subtler ways. The options open to Sweden’s Moderates illustrate the dynamics at play.

The slow growth of the SD has not been enough for it to form a government, as Fidesz, Syriza, a far-left party in Greece, and the Law and Justice party in Poland have done. But by 2014 it was big enough to make it hard for the established parties to form stable centre-left or centre-right coalitions, as was long their wont.

The Moderates might have joined a stodgily broad government of the centre right and left. Such governments have become much more common across the continent as the growth of populist parties, along with wider political fragmentation, has made more ideologically coherent coalitions harder to pull off. Today Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain offer variations on this muddled-middle theme, some of them formal coalitions, some looser toleration agreements. Such arrangements are unappealing for ambitious politicians. They also pep up populist rhetoric by proving that the political class is indeed all in it together.

The other two options available to the Moderates were to co-opt the populists or to try to steal their voters. Last March Anna Kinberg Batra, Mr Reinfeldt’s successor as leader, leant towards co-option, announcing that after next September’s election she might try to form a government with SD support. This prompted furious arguments which led to her resignation. Ulf Kristersson, the new leader, moved the party towards option two: “In Sweden we speak Swedish,” he declared pointedly in his Christmas message. But an SD-backed Moderate government is still possible.

Such possibilities do more than anything to normalise parties like SD. Austria, Bulgaria, Denmark, Finland, Latvia, the Netherlands and Norway have all now seen mainstream parties govern with the formal or informal support of populist parties. In Slovakia a government led by the centre left has a similar arrangement. The number of European governments with populists in their cabinets has risen from seven to 14 since 2000. Their ranks may soon be joined by the Czech Republic and Denmark, where the centre-right Venstre party says it might invite the right-populist Danish People’s Party (DPP), now propping it up in government, to become a full partner after the next election, which has to be held by July 2019.

The left is looking at new alliances, too. Last year, for the first time, Germany’s Social Democrats (SPD) went into a general election without ruling out a coalition with Die Linke, a left-populist party descended from the East German communists. Similarly, Spain’s centre-left Socialists have flirted with a deal with Podemos, a movement which grew out of anti-austerity street protests.

This all suggests the populist tide will continue to rise. Through analysing 296 post-1945 European elections, Joost van Spanje of the University of Amsterdam has found that, in general, welcoming formerly ostracised parties into the mainstream tends not to reduce their support.

The sincerest flattery

Going hand in hand with normalisation-by-coalition—in part its cause and in part its effect—is a growing professionalism and a professed moderation among the populists. In their early days they were often closely associated with frank racism, as with the anti-Semitism of the FN in the days of Ms Le Pen’s father; such sentiments are now increasingly kept at arms length (though in the case of Mr Orbán’s attacks on Mr Soros not very convincingly). They were also chaotic and split-prone. Some, like the UK Independence Party (UKIP), still are. Others, tasting or scenting power, have been getting their act together. The FPÖ in Austria is an example. It was shambolic during its previous turn in government, from 2000 to 2007, but it returned to ministerial power last December with a more sober image, having made efforts to distance itself from the right-wing Austrian social networks known as “fraternities”. “I expect the FPÖ to be much more disciplined and effective this time,” says Mr Mudde.

Part of this sprucing up involves tailoring policies to broaden support, which normally comes from the working class. While voters for Podemos, M5S and Syriza tend to be more educated than average, and also younger, the best predictor of support for the right-populists of the north is usually how early an individual left formal schooling. Winning over more bourgeois voters means tempering their message in some ways. Thus the FPÖ is less stridently anti-EU than it was. The same is true of the FN—which now presents itself as a staunchly pro-Israel bulwark against Islamism—the Danish DPP and the AfD.

Another part is experience gained in state governments and running municipalities like Wels, near Linz; subnational politics offers a good way to gain acceptability. City government in the north of Italy has helped the populists of the Northern League; in Spain mayors allied to Podemos in Madrid and Barcelona have given the party a stronger national profile. But local power is not always a plus. Corruption scandals and piles of rubbish in the streets of Rome under mayor Virginia Raggi have damaged M5S.

Austria’s new government also exemplifies the second sort of populist-mainstream accommodation: copying the populists’ ideas. In the election campaign the established Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP)—now the senior party in the coalition—shamelessly ripped off FPÖ policies, such as a burqa ban and reduced social-security rights for migrants. A cartoon in the Kurier, a newspaper, showed Heinz-Christian Strache, the FPÖ’s leader, naked in a police station: “They took everything!”

This “contagion”, as political scientists put it, is visible across the continent. Mark Rutte, the liberal-conservative Dutch prime minister, has pioneered a style of politics he distinguishes from “the wrong kind of populism”. Before last year’s election his party, pressed by the PVV and the Forum for Democracy, a new nationalist-populist party, ran dog-whistle adverts in newspapers telling foreigners to “behave normally or go away”. In 2016 Theresa May, his British counterpart, rallied her party by attacking “citizens of nowhere” who “find your patriotism distasteful, your concerns about immigration parochial, your views about crime illiberal, your attachment to your job security inconvenient” in a speech that could have come from UKIP. In December France’s Republicans chose as their leader Laurent Wauquiez, a Eurosceptic opposed to gay marriage who wants immigration reduced to “a strict minimum” and plans to make his party “truly right-wing”. New Democracy in Greece and GERB in Bulgaria, facing competition from the extreme-right Golden Dawn and Zankina parties respectively, have taken tougher lines on immigrants and other out groups.

In Germany the notionally liberal Free Democrats have called for most refugees to be sent back eventually. In Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats (CDU) there is talk of a more assertive German “lead culture” and a stronger sense of “homeland”, which may indicate the party’s direction when Mrs Merkel steps down. At the annual gathering in January of the Christian Social Union, the CDU’s Bavarian sister party, Mr Orbán was a guest of honour. Alexander Dobrindt, a CSU grandee, demanded a “conservative revolution” against Germany’s metropolitan minority.

One rationale for such cosying up is that it denies the populists exclusive ownership of sensitive issues such as identity, thus allowing reasonable voters to whom such issues matter an alternative not tinged with extremism. But in “The European Mainstream and the Populist Radical Right”, a new book, Pontus Odmalm and Eve Hepburn of the University of Edinburgh conclude that there is “no immediate pattern” suggesting that the availability of mainstream alternatives to the populist right weakens the latter's electoral performance.

Mr van Spanje’s analysis suggests that imitating populist insurgents only weakens them in the rare cases where they are also ostracised. Pointing to the dynamic between UKIP and Britain’s Conservatives before the Brexit referendum, Tim Bale of Queen Mary University of London observes that “the centre right often primes the electorate for the radical right’s message...helping it to take off and then, in an attempt to counter its appeal by talking even tougher, simply makes that message even more salient and further boosts its appeal.”

Meanwhile, on the left, social democratic parties are adopting what John Judis, an American journalist, calls “dyadic populism”. Insurgent populism often boasts three ideological players: the people, the elite, and the “other” (foreigners, immigrants, welfare spongers and the like) to whom the elite has sold the people out. Thus it is “triadic”. The dyadic version has no nefarious third party, just an us-and-them world where a corrupt capitalist political caste has betrayed the proletariat for its own benefit. Under Jeremy Corbyn, a 68-year-old from the party’s hard left, Britain’s Labour Party went into the 2017 election calling British politics a “cosy cartel” and a “rigged system set up by the wealth extractors, for the wealth extractors”. Martin Schulz, the SPD’s centrist leader, sought to protect his working-class flank in last year’s election by railing against bankers in “mirrored skyscrapers”.

Another way to get populist politics and policies without populist governments is to hold referendums. In 2013 Dutch populists keenly supported a law enabling any piece of primary legislation to be put directly to the country’s 12.9m voters if 300,000 of them demanded it. In Greece the Syriza government used a referendum to reject the conditions of a bail-out by international institutions. In Britain the referendum on Brexit—the fulfilment of a long-standing UKIP demand—compelled almost the entire political class to adopt a policy confined until recently to its populist fringes. Austria’s coalition agreement opens the door to more plebiscites; so, more tentatively, does the preliminary blueprint for a new CDU/SPD coalition in Germany. In Italy the M5S manifesto promises to give the people opportunities to vote on which laws to scrap.

Trilingualism against the triadics

Not all mainstreamers are parroting populist positions. The surge of what Mr Müller calls “illiberal democracy” has produced a backlash. The confidently pro-European, pluralist politics of Mr Macron and his En Marche! party is one instance. Another is the centrist Ciudadanos (“Citizens”) party now leading the polls in Spain. Its leader’s slogan is “Catalonia is my land, Spain my country and Europe is our future”—the first phrase spoken in Catalan, the second in Spanish, the third in English. Other new parties—Modern in Poland, Momentum in Hungary and NEOS in Austria—match the populists’ enterprise and presentational swagger while fighting their world view. As yet, though, they remain small.

It looks likely they will grow, but so will the sway of the populists. For a glimpse of what that may mean look at the continent’s last generation of political entrants: Green parties. Originally scrappy, over time they became more professional and started to join local and sometimes even national governments. None has ever led a European country alone, but their influence is felt in the attention now paid to green transport, recycling, renewable energy and certain civic liberties (particularly sexual freedoms).

What if the populists are as successful in the next few years? One might expect more authoritarian law-and-order policies, burqa bans, greater opposition to multilateral bodies like the EU, NATO and the WTO, and greater sympathy for Russia (an affection held across the populist spectrum, from Syriza to Fidesz by way of M5S). Expect, too, frequent referendums, less well integrated immigrants, more polarised political debates and more demagogic leaders emoting directly to and on behalf of their devoted voters.

Populists do not need to win elections to enact their policies and spread their style of politics.

They can do so through the very mainstream parties whose votes they threaten to take; infecting them and living off their political blood. “Eventually,” warns Mr Bale, “the parasite may end up consuming the host.”

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario