Peru

The troubling pardon of Alberto Fujimori

Presidential powers should not be used to undermine the rule of law

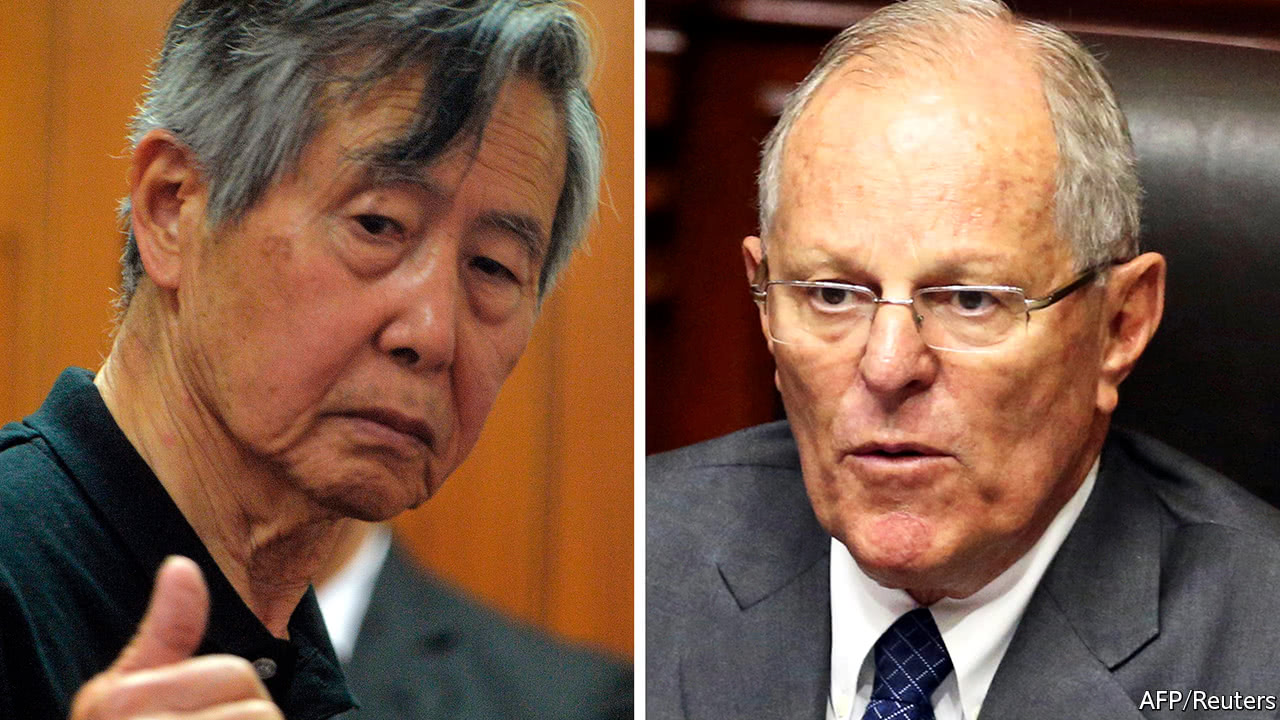

ON THE evening of December 24th, as Peru was preparing for its Christmas dinner, Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, the country’s president, bestowed an unexpected present on a jailed predecessor, Alberto Fujimori: a pardon. This came just three days after Mr Kuczynski hung on to his job thanks to ten fujimorista legislators led by Alberto’s son, Kenji, who abstained in a vote on an attempt to impeach him for links to Odebrecht, a tainted Brazilian construction firm. Mr Kuczynski insisted that the pardon was for “humanitarian reasons”. Few Peruvians believe him. More likely, it was a grubby political deal that bodes ill for his country (see article). Many of his allies feel as conned by this pardon as people who bought fake relics from Chaucer’s pardoner in “The Canterbury Tales”.

More than 15 years after the collapse of his decade of autocratic rule, Alberto Fujimori continues to divide his country. His supporters say he saved Peru from hyperinflation and Maoist terrorism and set it on the path of sustained economic growth. For his critics, he was a dictator who shut down congress, destroyed checks and balances, engaged in bribery and was complicit in a death squad. Both are right. But what is indisputable is that Mr Fujimori broke the law. He was found guilty in trials that were legally impeccable. His imprisonment was a landmark for Latin America, a message that all should be equal before the law in a region where the norm has too often been impunity for the rich and powerful.

Mr Fujimori has served more than ten years in jail (though that is less than half his sentence). He is 79, has a heart condition and is in remission from cancer of the tongue. Mr Kuczynski’s government has been dogged by the vengeful attitude of Keiko Fujimori, Alberto’s daughter, who narrowly lost the past two elections and who was behind the (disproportionate) attempt to impeach the president.

In principle a humanitarian pardon could have been part of a coherent plan of national reconciliation. But that was not Mr Kuczynski’s approach. The pardon was rushed, and backed by questionable medical evidence (there is no reason to think that Mr Fujimori is at death’s door). The government made no effort to consult the victims of Mr Fujimori’s rule, nor to seek a genuine apology from him. Alternatively, a pardon could have been more Machiavellian: a bargaining chip that Mr Kuczynski might have traded for fujimorista support for the institutional reforms—of the judiciary, the civil service and the political system—that Peru badly needs. There is no sign of that either. Instead, it looks like a sordid bargain to let the president survive.

A hostage of the Fujimoris

From the start, Mr Kuczynski, a businessman and economist, was an accident waiting to happen. He has neither political skills nor, seemingly, any awareness of his lack of them. He won office only because of anti-fujimorista sentiment; in defending himself from impeachment he railed against a fujimorista “coup”. Yet he has now made himself the fujimoristas’ hostage: few of his original supporters will now defend him, especially if it transpires that his dealings with Odebrecht involved more than an undeclared conflict of interest. He would have done better to resign and trigger an early election.

The pardoning of Mr Fujimori came days after a similar effort by Michel Temer, Brazil’s stand-in president. He abused the traditional Christmas exercise of presidential indulgence to try to free political cronies jailed for corruption, but the supreme court stood in his way.

Thanks to the efforts of prosecutors and judges in places like Brazil and in cases like Mr Fujimori’s, Latin America is starting to enjoy the rule of law. Presidents should not use the power of pardon to undermine it.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario