Consumers and Businesses Buckle under their Debts

by Wolf Richter

Bankruptcies surge as the “credit cycle” exacts its pound of flesh.

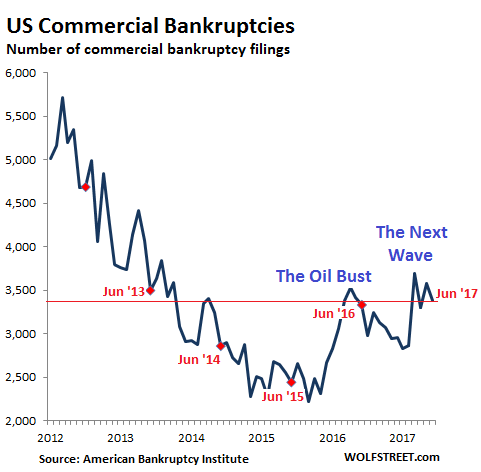

Commercial Chapter 11 bankruptcies – an effort to restructure the business, rather than liquidating it – jumped 16% year-over-year in June to 581 filings across the US. Total commercial bankruptcies of all types, by large corporations to tiny sole proprietorships, rose 2% year-over-year to 3,385 filings, according to the American Bankruptcy Institute. This was up 39% from June 2015 and up 18% from June 2014.

Commercial bankruptcies topped out at 9,004 in March 2010. By that time, credit conditions had been easing for a year, and liquidity was chasing yield. Not much later, even zombie companies – if they were large enough – were able to refinance their debts and borrow more to fund their operations and keep creditors happy. Bankruptcies fell sharply: In September 2015, they bottomed out at 2,217 filings.

Then the energy bust hit. Oil-and-gas companies along with coal companies began toppling, and bankruptcy filings surged. But in 2016, oil prices more than doubled off their lows. New money began pouring into the sector again. And drillers that had been cash-flow negative for two decades and had lost dizzying piles of money were able to refinance their debts and get new money to drill into the ground and live another day. And the waves of energy bankruptcies receded.

But now the next wave is building, with large and small retail operations at the forefront. I’ve covered only the largest chains of the brick-and-mortar meltdown, but there are many smaller operations, mom-and-pop stores, fashion shops, and the like that have quietly given up.

Bankruptcies are very seasonal, with peaks around the end of tax season and sharp declines in the following months. The data, which is not seasonally adjusted, gives a raw and noisy impression of how businesses are faring in this economy.

This chart shows the total number of commercial bankruptcy filings of all types. Note the strong seasonality. Hence, the year-over-year comparisons in red:

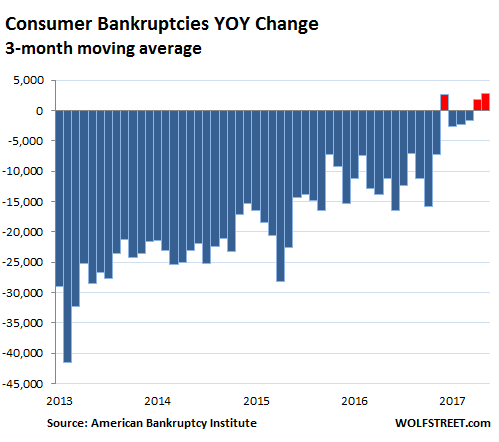

Consumer bankruptcy filings followed a similar pattern, but the turning point occurred a year later – in December 2016 and January 2017 – and was less obvious. Bankruptcy filings rose year-over-year in both months, the first back-to-back increase since 2010. I called it an “early red flag” at the time.

But consumer bankruptcy filings are volatile on a monthly basis, and turning points can take a while to be confirmed. In February, filings fell year-over-year. In March, they surged. In April they fell. But contrary to prior seasonal patterns, they surged in May. And in June, they ticked up 0.6% year-over-year to 63,372.

To filter out some of the monthly noise, I’ve created this chart using a three-month moving average of the year-over-year changes in the number of filings:

The chart shows the trend since 2013: Sharp year-over-year decreases in bankruptcies as consumers recovered from the Financial Crisis. The decreases gradually tapered off, as would be expected – bankruptcies are not going to fall to zero. But now a new phase has commenced: year-over-year increases in bankruptcies.

Clearly, consumers aren’t yet all of them together collapsing under their debts in one fell-swoop, but the “early red flag” is being confirmed as more and more consumers are buckling. Data on consumer delinquencies and defaults, particularly in subprime auto loans, has been cropping up for a year. Now it is filtering into bankruptcies.

“The economic challenges weighing on the balance sheets of struggling consumers and companies, especially retail businesses, have them seeking the financial shelter of bankruptcy,” observed ABI Executive Director Samuel Gerdano.

So the credit cycle has turned for both, businesses and consumers. This was inevitable. Credit cycles always turn. Easy money has much to do with it. It encourages borrowing for consumption or to fund business losses or unproductive investments. Years of too much borrowing lead to difficulties in servicing these debts and eventually to big losses for creditors.

Consumers seeking bankruptcy protection are those with piles of debt they can no longer handle, given their stagnating or declining real incomes, or perhaps the loss of income. This data shows that more consumers are facing these conditions, and the first wave is throwing in the towel.

Mortgages are not the cause. Home prices have been surging for years. By now, most homeowners can sell the home and pay off the mortgage. And if they can’t, and the bank forecloses on the property, it will rarely try to obtain a deficiency judgment in the 38 or so “full recourse” states where it is allowed. And in the dozen “non-recourse” states, the bank cannot even try.

The $1.4 trillion in student loans, though they now have sizzling default rates, are not the cause for bankruptcy filings either because they cannot be discharged in bankruptcy. But they contribute to driving people into bankruptcy.

Medical debts play a role – but not in the increase in bankruptcy filings. Some bad luck and one major emergency-room type event, without insurance, followed by a six-digit rip-off bill will do the job. But unless unemployment surges, the level of medical bankruptcies doesn’t move with the credit cycle and remains fairly constant.

The primary causes for the increase in filings are the $1.12 trillion in auto loans, the $1 trillion in credit card debts, and other consumer loans. Those loans fired up consumer spending in prior years.

Now the bill is coming due.

Commercial bankruptcies topped out at 9,004 in March 2010. By that time, credit conditions had been easing for a year, and liquidity was chasing yield. Not much later, even zombie companies – if they were large enough – were able to refinance their debts and borrow more to fund their operations and keep creditors happy. Bankruptcies fell sharply: In September 2015, they bottomed out at 2,217 filings.

Then the energy bust hit. Oil-and-gas companies along with coal companies began toppling, and bankruptcy filings surged. But in 2016, oil prices more than doubled off their lows. New money began pouring into the sector again. And drillers that had been cash-flow negative for two decades and had lost dizzying piles of money were able to refinance their debts and get new money to drill into the ground and live another day. And the waves of energy bankruptcies receded.

But now the next wave is building, with large and small retail operations at the forefront. I’ve covered only the largest chains of the brick-and-mortar meltdown, but there are many smaller operations, mom-and-pop stores, fashion shops, and the like that have quietly given up.

Bankruptcies are very seasonal, with peaks around the end of tax season and sharp declines in the following months. The data, which is not seasonally adjusted, gives a raw and noisy impression of how businesses are faring in this economy.

This chart shows the total number of commercial bankruptcy filings of all types. Note the strong seasonality. Hence, the year-over-year comparisons in red:

Consumer bankruptcy filings followed a similar pattern, but the turning point occurred a year later – in December 2016 and January 2017 – and was less obvious. Bankruptcy filings rose year-over-year in both months, the first back-to-back increase since 2010. I called it an “early red flag” at the time.

But consumer bankruptcy filings are volatile on a monthly basis, and turning points can take a while to be confirmed. In February, filings fell year-over-year. In March, they surged. In April they fell. But contrary to prior seasonal patterns, they surged in May. And in June, they ticked up 0.6% year-over-year to 63,372.

To filter out some of the monthly noise, I’ve created this chart using a three-month moving average of the year-over-year changes in the number of filings:

The chart shows the trend since 2013: Sharp year-over-year decreases in bankruptcies as consumers recovered from the Financial Crisis. The decreases gradually tapered off, as would be expected – bankruptcies are not going to fall to zero. But now a new phase has commenced: year-over-year increases in bankruptcies.

Clearly, consumers aren’t yet all of them together collapsing under their debts in one fell-swoop, but the “early red flag” is being confirmed as more and more consumers are buckling. Data on consumer delinquencies and defaults, particularly in subprime auto loans, has been cropping up for a year. Now it is filtering into bankruptcies.

“The economic challenges weighing on the balance sheets of struggling consumers and companies, especially retail businesses, have them seeking the financial shelter of bankruptcy,” observed ABI Executive Director Samuel Gerdano.

So the credit cycle has turned for both, businesses and consumers. This was inevitable. Credit cycles always turn. Easy money has much to do with it. It encourages borrowing for consumption or to fund business losses or unproductive investments. Years of too much borrowing lead to difficulties in servicing these debts and eventually to big losses for creditors.

Consumers seeking bankruptcy protection are those with piles of debt they can no longer handle, given their stagnating or declining real incomes, or perhaps the loss of income. This data shows that more consumers are facing these conditions, and the first wave is throwing in the towel.

Mortgages are not the cause. Home prices have been surging for years. By now, most homeowners can sell the home and pay off the mortgage. And if they can’t, and the bank forecloses on the property, it will rarely try to obtain a deficiency judgment in the 38 or so “full recourse” states where it is allowed. And in the dozen “non-recourse” states, the bank cannot even try.

The $1.4 trillion in student loans, though they now have sizzling default rates, are not the cause for bankruptcy filings either because they cannot be discharged in bankruptcy. But they contribute to driving people into bankruptcy.

Medical debts play a role – but not in the increase in bankruptcy filings. Some bad luck and one major emergency-room type event, without insurance, followed by a six-digit rip-off bill will do the job. But unless unemployment surges, the level of medical bankruptcies doesn’t move with the credit cycle and remains fairly constant.

The primary causes for the increase in filings are the $1.12 trillion in auto loans, the $1 trillion in credit card debts, and other consumer loans. Those loans fired up consumer spending in prior years.

Now the bill is coming due.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario