Donald Trump meant everything he said

.

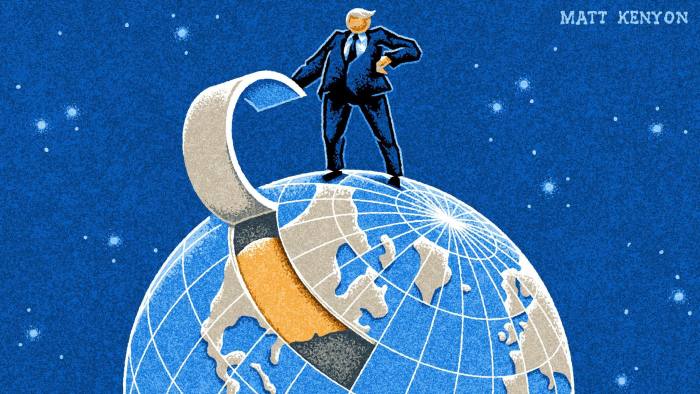

The New Economy involves phasing out all aspects of the old, including personnel

.

by: Christopher Caldwell

Globalisation is sucking the lifeblood out of the American yeomanry, one decaf mocha extra-skim Frappuccino at a time: anyone surprised that US President Donald Trump feels this way did not pay much attention to last November’s election.

Yet Friday’s inaugural address seems to have thrown Mr Trump’s adversaries into a state of shock. It turns out he actually meant those things. He spoke of “America first” as his principle; “protection” as his policy and “buy American” as his motto. Millions gathered on Saturday in cities across the country and globally for “women’s marches” to protest against his presidency. Mr Trump accepts the radical implications of his world view. In fact, he has a good chance of enacting it.

That Mr Trump’s oratory has the power to shock is a vindication of sorts. His campaign was about things that are invisible to ruling-class America, starting with non-ruling class America. Invisibility, anonymity, voicelessness was the theme of the whole speech: “One by one, the factories shuttered and left our shores,” he said, “with not even a thought about the millions and millions of American workers that were left behind”.

This sentence sounds like it is about deindustrialisation, but it is just as much about rulers’ hubris. The climax of the speech is: “Hear these words: You will never be ignored again.” Mr Trump thus proposes a new identity for the ruling class: not as compassionate champions of the excluded, not as bold captains of industry, not even as thoughtful defenders of common decency — but as pigs at the trough.

Almost every newspaper writer is convinced Mr Trump’s remarks were a vulgar embarrassment. That is a rash judgment. In a country where marketing patter is the lingua franca and most of the 324m residents have a knack for it, Mr Trump has just run the single most effective marketing campaign that any American ever ran for anything.

If you pay attention to the speech, it sounds less like a rant and far more like a serious governing programme. One phrase — “This American carnage stops right here and stops right now”— has struck people as a reference to slum violence, and indeed that is what it would have meant had a president used it a generation ago.

But its position in the speech makes it likely that Mr Trump is alluding to the wave of overdoses, mostly involving heroin and other opioids, in suburbs and small towns. This is the deadliest US drug crisis ever. It is killing 50,000 Americans a year, more than guns or motor vehicles do. In the 1970s, Curtis Mayfield sang about drugs and crime in the ghetto. In the 1980s, two presidents waged a “war on drugs”.

Today’s overdoses are beneath the notice of either the government or the culture. Mr Trump ran a strong campaign in New Hampshire and West Virginia, the two hardest-hit states.

Another widely misread phrase is “We have defended other nations’ borders while refusing to defend our own”. This does not, as many listeners assume, contradict Mr Trump’s promise elsewhere in the speech to “reinforce old alliances”. It attempts to re-establish the principle that countries have the right to defend their borders against not just armies but also immigrants.

Neglected, too, was Mr Trump’s resurrection of the 19th-century word “protection” as his preferred term for tariffs. Today it sounds as quaint as old disease names such as “consumption” and “dropsy.”

Usually we speak of protectionism, the presumably extremist ideology that opposes free trade. But Mr Trump is signalling that we are wrong to confuse the two. For him the difference between protection and protectionism is like the difference between Islam and Islamism. He is trying to make tariffs thinkable.

In fact he has already done so. Mr Trump has thrown a few gauntlets at the feet of corporate executives, and won. When General Motors announces a plan to invest $1bn in US jobs, as it did in the days before the inauguration, the sentiment can only rise among swing voters that Mr Trump must be right.

Ditto when the US’s European allies begin reprioritising budgets to bring defence expenditures to 2 per cent of GDP. In the wake of Mr Trump’s election, Lars Løkke Rasmussen, the Danish prime minister, promised to raise budgets. Formerly truculent Lithuania promised to bring its defence expenditures up to the Nato-standard 2 per cent of GDP by 2018, two years earlier than promised.

There is nothing especially radical about Mr Trump’s diagnosis of globalisation, except that he seems sincere about it. Every western politician of the past 20 years, from Hillary Clinton to Helmut Kohl to Jeremy Corbyn, has bemoaned that it leaves people behind. But they did not understand that the New Economy was a new economy. It involved phasing out every aspect of the old economy, including its personnel.

The theorists of the New Economy said it should be possible to compensate the “losers”. But that never happened. Because when the money came in, the people who managed the new economy did not recognise the losers as belonging to the same community.

Perhaps the surprise is that it took as long as it did for a US politician to argue that, if the system’s leaders cannot be trusted to reform it from within, they must be ordered to do so from without.

The writer is a senior editor at the Weekly Standard and is writing a book on the rise and fall of the post-1960s political order.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario